The contemporary defense and security relations between Türkiye and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states date back to the 1980s. However, the nature and scope of these ties have undergone a dramatic transformation since the Justice and Development Party (AKP) rose to power in Türkiye in 2002. Driven by shared security concerns and regional instability, the Türkiye-GCC relationship has significantly evolved over the last decade. Both Türkiye and the GCC nations recognize the need to enhance their defense capabilities in response to emerging threats, including geopolitical rivalries and the influence of non-state actors.

This transformation, particularly pronounced in recent years, as defense and security ties between Türkiye and the GCC continue to strengthen, invites an exploration of the potential for decentering arms within their bilateral relations. Such an inquiry is critical to understand the broader context of their partnerships and to identify alternative avenues for cooperation beyond arms transfers. Before considering the possibility of a more diversified relationship, it is essential to examine the current role that arms play in shaping these interactions.

To that end, this memo investigates the extent to which arms-centric dynamics define the Türkiye-GCC relationship. By analyzing existing defense and security ties, we aim to provide a comprehensive overview of the integral role arms play in their strategic partnerships. Furthermore, understanding this dimension enables us to assess the feasibility of transitioning toward a more multifaceted relationship, contributing to a more stable and resilient regional framework.

This memo focuses on three key areas of cooperation: 1) Arms Transfers, 2) Recent Major Arms Deals, and 3) Defense and Security Agreements. Through this analysis, we draw conclusions and present recommendations concerning the decentering of arms, suggesting pathways to achieve more balanced ties.

Türkiye’s Arms Transfers to the GCC States

Türkiye is a relative newcomer to the Gulf defense market compared to established players such as the US, Russia, France, Germany, the UK, China, and Italy. However, it is an aspiring arms exporter. According to SIPRI data for the period 2014-2018, the GCC states played a significant role in Türkiye’s arms exports, accounting for a substantial portion of total arms transfers. Notably, three out of Türkiye’s top 10 defense industry customers were from the GCC (see Table 1).

Saudi Arabia ranked second overall in terms of arms imports, comprising 14% of Türkiye’s total exports during this period, underscoring its centrality to Türkiye’s defense market. In total, the GCC nations collectively made up 28.2% of Türkiye’s defense exports, highlighting the strong defense ties between Türkiye and the Gulf states.

Table 1: Türkiye’s Arms Transfers (2014-2018)

Millions of SIPRI’s TIVs

Recipient | Rank | Amount | Percentage |

Saudi Arabia | 2 | 143 | 14% |

Qatar | 5 | 65 | 6.20% |

Oman | 8 | 44 | 4.20% |

UAE | 11 | 15 | 1.40% |

Bahrain | 12 | 14 | 1.30% |

Kuwait | 13 | 12 | 1.10% |

Source: SIPRI Database

In the period 2019-2023, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Egypt, UAE, and Israel were the largest arms importers in the Middle East. According to 2024 SIPRI data, Türkiye became the 2nd largest arms exporter from the Middle East and the 11th largest exporter in the world, with 1.6% of the global arms exports.1 During this period, the GCC countries saw shifts in their rankings and defense imports from Türkiye. (See Table 2)

The UAE rose to the 1st place, increasing its share of Ankara’s arms exports from 1.4% to 15%. SIPRI data indicates the UAE significantly boosted its purchases from Türkiye, from 0.3% in 2014-2018 to 9.9% in 2019-2023, making Türkiye the 2nd largest arms supplier to the UAE.2

Similarly, Qatar rose to 2nd place with 13% of Türkiye’s arms exports, remaining one of the largest defense partners. During this period, Qatar’s arms purchases from Ankara accounted for 2.9% of its imports in comparison to 3% in 2014-2018, making Türkiye the 6th largest arms exporter to Qatar.3

Saudi Arabia, however, experienced a significant drop, falling from 2nd to 31st place during the 2019-2023 period, with Türkiye’s exports to Saudi Arabia accounting for just 0.2% of its total exports. This represented nearly 0% of Riyadh’s arms imports, compared to 0.9% in the previous period.

The overall trend from 2019-2023 shows that the UAE and Qatar solidified their positions as Türkiye’s primary arms importers among the GCC states, while Saudi Arabia fell from 2nd to 31st place. Bahrain dropped from 12th to 16th, and Kuwait saw a major decline from 13th to 42nd.

Table 2: Türkiye’s Arms Transfers (2019-2023)

Millions of SIPRI’s TIVs

Recipient | Rank | Amount | Percentage |

UAE | 1 | 328 | 15% |

Qatar | 2 | 293 | 13% |

Oman | 6 | 157 | 7.20% |

Bahrain | 16 | 28 | 1.30% |

Saudi Arabia | 31 | 5 | 0.20% |

Kuwait | 42 | – | 0.00% |

Source: SIPRI Database

Over the longer period from 2014 to 2023, the importance of GCC states in Türkiye’s arms exports remains evident, with four of the six GCC states ranking in the top 10. Qatar leads in 3rd place, followed closely by the UAE in 4th and Oman in 6th place. Saudi Arabia ranks eighth place, Bahrain holds the 14th position, and Kuwait occupies 30th place. This period highlights the GCC region’s ongoing role as a key market for Türkiye’s arms exports, though the dynamics among individual states have shifted significantly. (See Table 3) Qatar and the UAE have become dominant players, solidifying their positions as Türkiye’s top GCC customers, while Oman has maintained a steady relationship. Saudi Arabia has remained in the top 10, whereas Bahrain and Kuwait lag far behind.

Table 3: Türkiye’s Arms Transfers (2014-2023)

Millions of SIPRI’s TIVs

Recipient | Rank | Amount | Percentage |

Qatar | 3 | 358 | 11% |

UAE | 4 | 343 | 11% |

Oman | 6 | 201 | 6.20% |

Saudi Arabia | 8 | 148 | 4.60% |

Bahrain | 14 | 42 | 1.30% |

Kuwait | 30 | 12 | 0.40% |

Source: SIPRI Database

Major Türkiye- GCC States Arms Deals

While arms transfers indicate active cooperation, recent major arms deals provide critical insights into the broader political landscape and potential future trends, assuming the relationship between Türkiye and the GCC continues on a stable trajectory. Over the past two years (2022-2024), arms agreements between the GCC states and Türkiye accelerated significantly.

In 2022, the UAE reportedly offered a contract worth around $2 billion to buy 120 Turkish Bayraktar TB2 drones. This deal marked a strategic move by the UAE to solidify its role in Gulf military strategy and suggested a growing alignment of interests between Türkiye and the UAE, despite past political tensions.

In June 2023, Kuwait placed an order worth $367 million for Turkish TB2 drones.4 This deal highlighted Kuwait’s increasing openness to arms imports from Türkiye following the resolution of the 2017 GCC crisis, reflecting a broader regional trend in the Gulf.

In July 2023, Saudi Arabia reportedly signed a $3 billion arms deal, the largest in the history of Türkiye’s defense industry, to acquire an undisclosed number of state-of-the-art AKINCI Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicles (UCAVs).5 The magnitude of this deal signaled a shift in the previously strained relations between Saudi Arabia and Türkiye, marking a major step in their military ties and potentially paving the way for more large-scale defense cooperation in the future.

Additionally, Haluk Görgün, head of the Presidency of Defense Industries (SSB),6 revealed that one of the Arab Gulf states was in talks with Ankara to acquire a Light Aircraft/UCAVs Carrier (LAC), similar to Türkiye’s new flagship TCG Anadolu (L-400), worth at least $1 billion (in 2015 prices). Given the size and operational demands of the carrier, the likely buyer is either Saudi Arabia or the UAE.7

Türkiye – GCC Countries Defense and Security Agreements

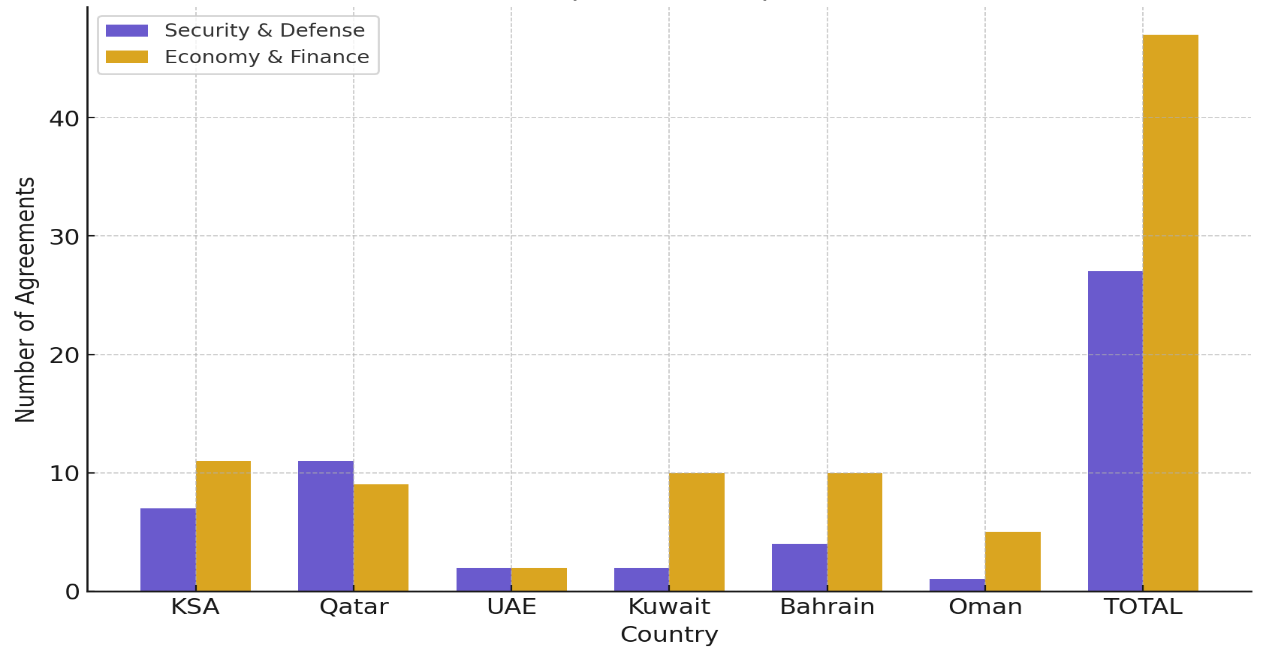

Based on a research project conducted by the author in 2022, the investigation reveals that Türkiye and the GCC countries have entered into 27 ratified bilateral defense and security agreements, including Memorandums of Understanding, laws, and technical agreements.8

These agreements can be primarily categorized into six areas:9 1) Military cooperation, including training, education, and scientific collaboration; 2) Security cooperation, focused on countering terrorism, smuggling, and drugs, as well as training relevant authorities and forces; 3) Defense industry cooperation; 4) Military exercises; 5) Military health; and 6) Financial intelligence.

In addition to these categories, the deployment of forces agreement between Türkiye and Qatar holds a unique position, standing apart from the others due to its distinct nature.

Analyzing the timeline of both the signing and ratification of these agreements reveals that they are typically motivated by or respond to major security developments in the region. One significant development was the rise of Israeli and Iranian threats after 2006. The Israeli-Hezbollah war that year marked a shift in regional power dynamics, with both Iran’s growing influence and Israel’s strategic posture pushing Gulf countries and Türkiye to enhance their security and defense capabilities.

The 2011 Arab Uprisings also triggered widespread instability across the Middle East, leading several GCC states to reassess their security partnerships, including those with Türkiye. Shared concerns about instability, terrorism, and regional rivalries accelerated the strengthening of formal defense ties during this period, especially with Qatar.

The 2015 nuclear deal between the US and Iran, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), heightened anxiety among GCC countries over Iran’s regional influence, prompting them to seek stronger defense cooperation with regional powers like Türkiye.

The 2017 GCC crisis, involving Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, and Qatar, reshaped the Gulf’s security environment and affected relations within the GCC. Türkiye’s defense relationship with Qatar deepened during this period, resulting in the deployment of Turkish forces in Qatar and a notable increase in arms imports from Türkiye.

The 2021 Al-Ula agreement, which formally ended the 2017 GCC crisis and the blockade imposed on Qatar, ushered in a new era of reconciliation and normalization within the Gulf and beyond. This development provided fresh opportunities for defense and security collaboration across the GCC and with Türkiye, even as concerns about Iran, Israel, and other external threats remained.

When comparing the number of defense and security agreements between Türkiye and the GCC states to those in other sectors, such as the economy, it appears that there are much less defense and security agreements, accounting for about 57% of the number of economic agreements. At a bilateral level, defense and security agreements also rank second, except in the case of Qatar, where the number of defense and security agreements exceeded that of economic ones.

Figure 1: GCC Countries’ Ratified Agreements with Türkiye (2002-2022)

Source: The author (Ali Bakir), based on an unpublished paper from a 2022 project

Observation and Analysis

Overall, defense ties, arms transfers, and arms contracts are driven by Türkiye’s desire to sustain and grow its indigenous defense industry. This strategy aims to enhance the defense sector’s contribution to the national economy and increase hard currency revenue. Strengthening defense and security ties with importing countries also serves to deepen economic and political relationships.

On the part of the GCC countries, motivations may vary by case, but generally include the desire to diversify their defense and military ties, strengthen their security posture, develop their own indigenous defense industries, and make business decisions that efficiently meet their defense needs in a relatively affordable manner.

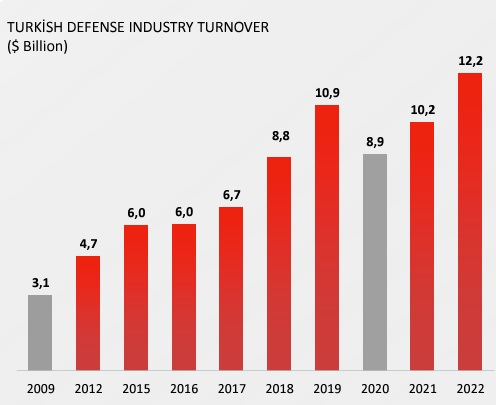

While Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Oman, Qatar, and Bahrain collectively accounted for approximately 34.5% of Türkiye’s total defense exports from 2014 to 2023, the dollar equivalent of this percentage remains relatively small. Notably, Türkiye’s defense industry market did not exceed $6 billion until 2018. (See Figure 2)

Figure 2: Türkiye’s Defense Industry Turnover

Source: Turkish Defense & Aerospace Industry 2022,

Presidency of the Republic of Türkiye

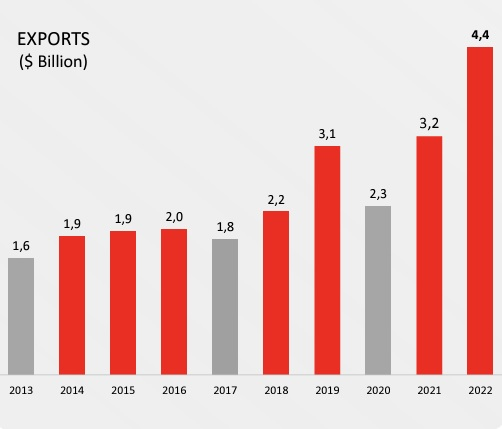

According to Turkish official figures, the country’s total defense arms exports during the period 2014-2023 were valued at around $28.3 billion,10 (see Figure 3), which translates to an annual average of approximately $2.83 billion. This indicates that the value of GCC states’ purchases, either individually or collectively, represents a relatively small portion compared to the total arms imports of Gulf countries, their arms imports from Western allies, and Türkiye’s GDP.

Figure 3: Türkiye’s Defense Industry Exports

Source: Turkish Defense & Aerospace Industry 2022,

Presidency of the Republic of Türkiye

While the presence of Qatar and the UAE in the top 5 customers of Türkiye’s defense exports during the period 2014-2023 might not be surprising, Oman’s ranking in 6th place raises eyebrows, especially when a country like Saudi Arabia ranks only in 8th place. Oman’s arms imports during this period were initially driven by a large contract for 172 armored vehicles in 2015—the biggest ’deal a GCC country had signed with Türkiye at the time.11 This opened the door for joint ventures, such as the one established with HAVELSAN in 2020,12 followed by rumors of Oman potentially hosting a Turkish naval base.13

The small difference in the volume of Turkish defense exports to Qatar and the UAE during the period from 2014 to 2023 is also notable, with each country securing 11% of Türkiye’s defense exports. One might expect Qatar to surpass the UAE by a wide margin, given the advanced nature of defense and military ties between Doha and Ankara, which began in 2014 following the defense agreement that enabled Türkiye to deploy troops in Doha in 2017. However, this is not the case, and two reasons might explain this situation.

First, the UAE continued to import Turkish defense equipment even during periods of high tension with Ankara,14 primarily due to its involvement in the Yemen war and its willingness to engage in transactional relationships. This aspect of the UAE-Türkiye relationship is often overlooked in mainstream media, discussions, and research, which tend to emphasize tensions and conflicts between the two nations.

Second, Doha focused less on purchasing military equipment from Türkiye compared to the UAE and instead invested in joint defense industry projects and hosting the Turkish military base in Doha. These investments do not appear in arms export data and are therefore not captured by SIPRI figures. For instance, in 2019, the BMC Turkish defense company, which is partially owned by Qatar, was granted the right to operate one of the Turkish military’s premier tank and pallet factories for the next 25 years.15

Another noteworthy point is Saudi Arabia’s relatively low ranking at 8th place. In fact, if Riyadh had not ranked 2nd place during the period 2014-2018, its overall ranking for 2014-2023 would have been significantly lower – which is primarily related to two factors.

First, Saudi Arabia’s involvement in the Yemen war starting in 2015, combined with the Obama administration’s reluctance to supply it with ammunition and weapons at the time, led Riyadh to turn to Ankara. This—among other reasons—explains Saudi Arabia’s leading position in the 2014–2018 period.

Second, based purely on import/export valuesit appears that Saudi Arabia—unlike the UAE—was more inclined to halt arms trade during times of geopolitical disagreements and tensions with Türkiye. This helps explain why Saudi Arabia fell from 2nd to 31st place during the 2018–2023 period. For example, Saudi Arabia canceled an arms deal with Türkiye involving four warships worth $2 billion when the 2017 GCC crisis erupted.16 Normalizing ties between Riyadh and Ankara in recent years may help Saudi Arabia improve its position going forward.

There is no strong correlation between arms transfers, defense/security agreements, and economic ties. For instance, Kuwait has maintained the most stable relationship with Türkiye since 2002, yet its arms imports from Ankara are minimal. Qatar is the largest arms importer from Türkiye, yet non-military bilateral trade between the two countries remains limited. Saudi Arabia reportedly placed the largest defense contract in Türkiye’s history, yet its non-military bilateral trade with Türkiye is also limited. Oman, despite having limited economic ties with Ankara, at one point held the largest defense contract with Türkiye.

Concerning the correlation between arms deals/transfers and political ties, our observations suggest that good political relations often drive defense, military, and arms sales to higher levels. In other words, political ties act as a primary driver, rather than economic or security factors. Political tensions, on the other hand, significantly impact arms sales.17

Conclusion and Recommendation

Our observations indicate that the actual volume of GCC states’ arms imports from Türkiye is currently not substantial or central to the bilateral ties. However, given the undeniable strengthening of arms transfers, major deals, and defense and security ties between Türkiye and the GCC over the past three years—marked by significant arms sales and bilateral agreements—our analysis highlights the need to strike a balance between increasing arms sales and non-arms-centric initiatives for long-term stability, resilience, and a multi-layered relationship.

This balance could be achieved by focusing on non-military economic ties and addressing soft security and human security issues.18 For instance, Türkiye and the GCC could collaborate on climate resilience projects, which are becoming increasingly critical in the face of climate change.19 Joint initiatives in areas related to economic integration, as well as soft security measures like water security, food security, energy security, and cybersecurity, could complement traditional security measures and create a more comprehensive security framework. These initiatives would serve as essential strategic priorities for long-term stability in the region.

Additionally, because defense cooperation between Türkiye and the GCC remains reactive—often shaped by political dynamics, external factors, and the influence of established powers like the United States and the EU—an arms-centric relationship could fuel an arms race among various actors, further destabilizing the region. This would complicate Türkiye’s position and that of other GCC actors.

Moreover, since political dynamics can shift rapidly in the region, especially in the Gulf, an arms-centric relationship could hinder the development of more sustainable forms of cooperation. Therefore, initiatives focused on non-military cooperation would not only reduce vulnerabilities related to shifting political landscapes and the volatility of arms markets but also create a framework for addressing shared challenges beyond hard security. This would help decenter arms20 from Türkiye-GCC relations.

Ultimately, this approach would mitigate the risk of fostering an arms-centric relationship in the future while promoting a more balanced and sustainable partnership rooted in a broader spectrum of shared interests, contributing to a more stable and less volatile region.

1“Trends in International Arms Transfers, 2023,”, SIPRI, March 10, 2024. https://doi.org/10.55163/pbrp4239

22024 SIPRI data

3Ibid

4Bakir, Ali. “Turkiye’s defense industry is on the rise. The GCC is one of its top buyers”, Atlantic Council, August 4, 2023. www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/Turkiye-defense-baykar-gcc-gulf/

5Ibid

6The SSB is Turkiye’s Defence Industry Agency, known in Turkish as Savunma Sanayii Başkanlığı (SSB). Formerly, it was known as the “Undersecretariat for Defence Industries” (SSM). It is a civil institution established by the government to manage the Defence industry of Turkiye. In 2018, it was brought under the Turkish Presidency as a part of the reforms undertaken by the newly implemented Presidential System at the time.

7Ibid.

8Note that the ones that are not ratified are not counted here.

9The categorization is proposed by the author, drawing from both the title and the content of the ratified agreements.

10Calculated by the author based on official numbers (shown in the above figure) + figures from 2023 at this link: https://www.tccb.gov.tr/en/news/542/151299/-we-achieved-5-5-billion-in-defense-industry-exports-in-2023-

11Bakeer, Ali. “Will Geopolitical Instability Strengthen Omani-Turkish Relations?, Al Sharq Strategic Research, August 9, 2020. https://research.sharqforum.org/2018/10/05/will-geopolitical-instability-strengthen-omani-turkish-relations/

12“Havelsan Technology Oman LLC Officially Inaugurated”, Defence Turkey, April 2020. www.defenceturkey.com/en/content/havelsan-technology-oman-llc-officially-inaugurated-3933

13Bakir, Ali, “Turkey boosts military footprint in Qatar in shadow of Trump’s potential return”, Amwaj media, August 16, 2024. https://amwaj.media/article/turkey-boosts-military-footprint-in-qatar-in-shadow-of-trump-s-potential-return

14For example, UAE’s Tawazun’s contract with Turkye’s Otokar, which was signed just before the 2017-GCC crisis, was not canceled. Check: https://www.defenceturkey.com/en/content/otokar-s-world-class-status-reinforced-with-al-jasoor-the-gulf-region-s-rabdan-8×8-a-colossal-deal-brimming-with-new-market-opportunities-2595#:~:text=This%20is%20contract%20is%20Turkey’s,at%20UAE’s%20capital%20Abu%20Dhabi.

15Bakir, Ali. “Testing the Turkey-Qatar military partnership”, The New Arab, Feb. 25, 2019. www.newarab.com/opinion/testing-turkey-qatar-military-partnership

16“Saudi Arabia ‘Cancels $2 Billion Shipbuilding Contract’ with Turkiye.” The New Arab, May 30, 2017. www.newarab.com/news/saudi-arabia-cancels-2-billion-shipbuilding-contract-Turkiye

17The case of the UAE’s continued import of weapons from Ankara during tense relations is an exception with its own unique circumstances and cannot be generalized.

18Tartir, Alaa and Morsy, Ahmed. “The Securitization of Everyday Life: Where are the People?”, PRISME, Summer 2023. https://prismeinitiative.org/blog/securitization-of-everyday-life-alaa-tartir-ahmed-morsy/

19De Vries, Wendela. “Arms trade; lost opportunity for climate solutions”, PRISME, Fall 2023. https://prismeinitiative.org/blog/arms-trade-lost-opportunity-for-climate-solutions-wendela-de-vries/

20Soubrier, Emma. “The impacts of militarized foreign policy in the MENA region”, PRISME, July 2024. https://prismeinitiative.org/blog/impacts-militarized-foreign-policy-mena-region-emma-soubrier/