The Israeli nuclear arsenal has long served as a symbol of asymmetry in the Middle East’s security landscape.1 Owing to its exceptional and contested history, Israel’s nuclear status was securitised from the outset: Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states historically framed it as a threat to regional stability, a persistent obstacle to peace, a violation of the normative framework of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), and emblematic of broader double standards within the global non-proliferation regime. In line with this framing, GCC states have actively sought to maintain the salience of the Israeli nuclear issue on international diplomatic agendas as an unresolved security concern.

However, the formalisation of a new regional security architecture—most notably embodied in the 2020 Abraham Accords—has coincided with a marked shift in Gulf diplomatic discourse surrounding Israel’s nuclear posture.2 In particular, Omani, Bahraini, and Emirati diplomats have increasingly omitted references to Israel’s nuclear capabilities in their public and diplomatic statements. By contrast, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, albeit to differing degrees, continue to publicly criticise Israel’s nuclear status. While the Abraham Accords did not initiate this discursive shift, they served to accelerate an already unfolding trajectory. In this respect, the Accords should be seen not as a definitive “before and after” moment, but rather as a formal milestone in a broader process of diplomatic recalibration. Among the GCC states, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) have formally signed the Accords, while Oman and Saudi Arabia have engaged in varying degrees of informal alignment without full diplomatic normalisation. Kuwait and Qatar, on the other hand, have maintained a more oppositional and critical stance.

This shift—most clearly observable in the cases of Bahrain and the UAE—constitutes what may be termed a political act of ‘silencing’: a radical form of de-securitisation with long-term normative implications.3 In the fluid discursive terrain of Middle Eastern security politics, where narratives of threat, legitimacy, and stability are in constant negotiation, the deliberate omission of Israel’s nuclear status from diplomatic discourse signals more than a tactical adjustment. Rather, it points to an evolving reconfiguration of regional security imaginaries—one that privileges tacit acceptance over open confrontation. The act of silencing redefines the boundaries of what is deemed speakable within regional security politics, amounting to an effort to de-institutionalise and de-prioritise Israel’s longstanding policy of nuclear opacity.

Empirical Patterns: Who Speaks, and Who Falls Silent

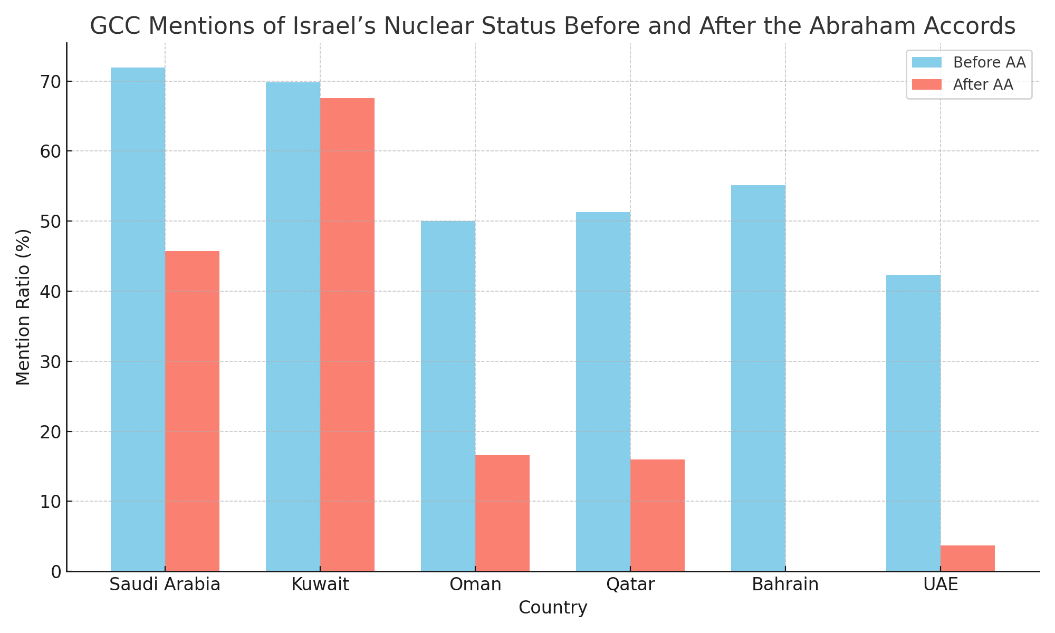

Despite shared regional dynamics, each GCC state demonstrates a distinct pattern of engagement with the Israeli nuclear issue. Variations are evident not only in the volume of participation in nuclear-related forums but also in the frequency and framing of references to Israel’s nuclear posture. Overall, the UAE and Kuwait emerge as the most active participants in multilateral nuclear diplomacy, whereas Oman displays the lowest level of overall engagement.4 However, levels of participation do not always correlate with the number of country-specific references to Israel’s nuclear status. When evaluated as aggregate mention ratios for the 2005–2024 period, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia consistently prioritised the Israeli nuclear issue in their diplomatic discourse. By contrast, Bahrain, Qatar, and Oman clustered around a more moderate average mention rate of approximately 42 per cent. The UAE has the lowest aggregate ratio of mentions (27%).

A comparison of these ratios before and after the signing of the Abraham Accords reveals significant shifts in the discursive practices of most GCC states.

Notably, Oman, Bahrain, and the UAE experienced a 100 per cent decrease in their respective mention ratios up to 2022, suggesting a comprehensive ‘silencing’ of the issue within their diplomatic rhetoric. Among these, Bahrain underwent the most pronounced transformation.

Prior to 2019, Bahraini diplomats routinely criticised Israel in nuclear disarmament fora, ranking third among GCC states in terms of pre-Accords mention rates. However, since 2019, Bahraini representatives have refrained from referencing Israel’s nuclear status altogether, despite maintaining active participation in relevant diplomatic venues. A comparison with earlier interventions, particularly from 2005, reveals a stark shift in both tone and framing. In that year, Bahrain’s representative employed explicitly condemnatory language, characterising Israel’s nuclear posture as marked by “refusal,” “indifference,” “arrogance,” and a “contradictory and hegemonic policy.”5 This early framing underscores a confrontational stance that has since been gradually abandoned. The subsequent silence coincides with Bahrain’s formal normalisation of relations with Israel under the framework of the Abraham Accords. Although Bahraini diplomats continue to engage with broader non-proliferation concerns—especially with regard to Iran—references to Israel have been systematically excluded from recent discourse.

The UAE presents a similarly compelling case. Between 2005 and 2018, Emirati diplomats consistently criticised Israel’s non-accession to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) and highlighted systemic double standards in the global non-proliferation regime. Yet, between 2019 and 2022, UAE representatives delivered 28 statements in nuclear fora without a single reference to Israel’s nuclear capabilities. Notably, references to Israel reappeared in 2023 and 2024, albeit in a markedly softened tone. Rather than employing accusatory language or framing Israel as a regional security threat, Emirati diplomats urged Israel to “join the NPT as a non-nuclear weapon state”—a formulation that subtly reinforces Israel’s self-representation as a responsible actor, despite its undeclared nuclear arsenal. This change in tone suggests a broader recalibration of the UAE’s diplomatic approach, likely influenced by the formalisation of bilateral ties through the Abraham Accords.

Although not a signatory to the Abraham Accords, Oman also exhibits a sharp decline in references to Israel’s nuclear status. From 2005 to 2019, Omani diplomats regularly criticised Israel’s nuclear ambiguity. However, between 2020 and 2023, Oman made no such references, despite continued engagement in nuclear diplomacy. This silence points to the broader regional effects of the Accords, suggesting that the discursive impact of normalisation extends beyond signatory states. Oman’s rhetorical shift may reflect an evolving regional consensus in which overt criticism of Israel’s nuclear policy is no longer seen as diplomatically expedient.

Qatar ranks third among GCC states in terms of individual contributions to nuclear forums during 2005–2024. In the years prior to the Abraham Accords, Qatari diplomats frequently invoked Israel’s nuclear programme in strongly critical terms, often highlighting the complicity of NPT member states and the destabilising effects of Israel’s nuclear opacity. However, Qatar remained silent on the issue in 2020 and 2021, despite maintaining active participation in nuclear diplomacy. This silence proved temporary; in 2022, Qatari representatives delivered a robust statement at the IAEA General Conference, calling on the Agency to pressure Israel into compliance with international norms. Unlike the sustained silence of Bahrain and the UAE, Qatar’s pause appears to reflect a momentary recalibration rather than a lasting discursive transformation. Nonetheless, even brief silences may indicate shifting normative constraints, wherein explicit criticism of Israel is no longer a consistent diplomatic feature—even for states that have not normalised relations with Israel.

By contrast, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia stand out as notable exceptions to the broader trend of rhetorical moderation or silence. Kuwait is the most consistent and vocal GCC critic of Israel’s nuclear programme, recording the highest aggregate mention ratio both overall and in the post-2020 period. Although there is a modest decline in references after 2020, Kuwaiti diplomats have continued to denounce Israel’s refusal to join the NPT, its lack of adherence to comprehensive IAEA safeguards, and its obstruction of efforts to establish a Middle East nuclear-weapon-free zone. Saudi Arabia also presents a notable case. Despite fewer individual interventions than Kuwait, it holds the second-highest aggregate mention ratio across the 2005–2024 period, and the highest pre-Accords ratio (71.9%). Saudi discourse on Israel’s nuclear status has remained relatively stable, with only a slight decrease after 2020. Even as broader regional trends point to discursive silencing, Saudi Arabia continues to consistently raise concerns over Israel’s nuclear posture, maintaining the highest frequency of such references among GCC states in the post-Accords period.

In sum, patterns of rhetorical silencing regarding Israel’s nuclear status vary markedly across the GCC. These differences are shaped by domestic political agendas, degrees of regional alignment, and evolving international pressures. The UAE and Bahrain, as signatories of the Abraham Accords, have generally toned down their condemnation of Israel, as exemplified by the statements issued in the aftermath of the Al-Ahli hospital explosion on October 17, 2023.6 In contrast, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait have been sharper in their condemnation of Israel. The narrative patterns concerning the Israeli nuclear issue are coherent with these broader trends. While the Abraham Accords represent a turning point for some states, others remain committed to voicing traditional criticisms—underscoring that silencing is neither uniform nor inevitable.

Conclusion

What are the implications of this discursive transformation? First, the political act of silencing Israel’s nuclear status risks entrenching the very exceptionalism that has long defined its regional posture. By removing the issue from diplomatic discourse, Bahrain, the UAE – and to a lesser extent Oman and Qatar – inadvertently legitimise the opacity they once condemned, thereby reinforcing Israel’s unique position outside the non-proliferation normative framework. It is understood here that this silence is also – first and foremost – sustained by the permissiveness of global actors: the United States and European powers have long tolerated Israel’s nuclear opacity, while international institutions such as the IAEA have refrained from directly confronting it.

Second, this silence does not occur in a vacuum. It is part of a broader erosion of accountability across the international system, reflected most starkly in the impunity surrounding Israel’s ongoing military campaign in Gaza. In this context, silence about Israel’s undeclared nuclear arsenal contributes to a wider pattern of normalisation – if not naturalisation. One must ask: what role does this emerging pattern of silencing Israel’s nuclear status play in sustaining regional hierarchies of threat perception?

Third, and related to this question, the silencing of Israel’s nuclear status coincides with the hyper-securitisation of other regional actors—most notably Iran. This asymmetrical treatment reflects a broader discursive pattern whereby securitisation dynamics surrounding Iran have intensified, as highlighted in Héloïse Fayet’s memo, even as discussions around Israel’s nuclear posture have progressively softened.7 This double standard further corrodes the credibility of the global non-proliferation regime and raises critical questions for the future of regional disarmament, particularly the viability of the Middle East WMD-free zone agenda. If opacity becomes de-problematised and de-securitised, the normative foundations of disarmament efforts may weaken irreversibly.

Silence is not absence—it is agency. In the GCC’s diplomatic discourse, the disappearance of references to Israel’s nuclear programme constitutes an active process of de-securitisation. It is a productive reordering of regional security imaginaries: one that redefines acceptable forms of nuclear asymmetry, reconfigures hierarchies of threat, and de-politicises opacity itself. Policymakers and scholars must take this transformation seriously. If silence becomes the default posture, it risks foreclosing critical pathways toward transparency, accountability, and eventual disarmament. The SALAM community—and the broader non-proliferation and disarmament network—should therefore interrogate not only what is said, but also what is unsaid. The politics of silence is the politics of power, and it is reshaping the nuclear future of the Middle East.

1On the legacy of inconsistent non-proliferation practices in the region see Almuntaser Albalawi, ‘From Asymmetry to Autonomy: Rethinking Arms Control in the Middle East’, PRISME Initiative, 2025; Hassan Elbahtimy, ‘Whose Nuclear Disorder? The Middle East in Global Nuclear Politics’, PRISME Initiative, 2025.

2This memo analyzes speeches delivered between 2005 and 2024 by the representatives of the six GCC countries in their national capacities in the following nuclear non-proliferation and disarmament fora: the IAEA General Conference (GC), the First Committee of the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA), the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) Review Conferences and Preparatory Committees, the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) Meeting of State Parties and Negotiating Conference, the Conference on the Humanitarian Impact of Nuclear Weapons series of conferences (Oslo 2013, Nayarit 2014, Vienna 2014), Conference on the Establishment of a Middle East Zone Free of Nuclear Weapons and Other Weapons of Mass Destruction, United Nations Disarmament Commission (UNDC), UNGA General Debate, United Nations Security Council (UNSC), the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (Article XIV Conferences), and Conference on Disarmament (High-Level Segment).

3Lene Hansen, ‘Reconstructing desecuritisation: the normative-political in the Copenhagen School and directions for how to apply it,’ Review of International Studies, Vol. 38, No. 3 (2012): 525-546, p.533.

4The UAE and Kuwait have the highest number of individual contributions to nuclear debates, especially in the years of non-permanent membership of the Security Council (Kuwait: 2018-2019; UAE: 2022-2023). Qatar was a non-permanent member in the period 2006-2007. Saudi Arabia was elected as a non-permanent member of the SC for the period 2014-2015 but did not accept it, see, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N13/566/29/PDF/N1356629.pdf?OpenElement. Oman and Bahrain were elected non-permanent members before 2005, respectively in 1994-1995 and 1998-1999. See, https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/content/countries-elected-members.

5UNODA, Statement by Bahrain, May 1, 2005 (in Arabic), Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons – Seventh Review Conference, https://www.un.org/en/conf/npt/2005/statements/npt04bahrain-arabic.pdf.

6‘Bahrain strongly condemns Israeli bombing of Al-Ahly Baptist Hospital in Gaza,’ Bahrain News Agency, October 17, 2023, https://www.bna.bh/en/BahrainstronglycondemnsIsraelibombingofAlAhlyBaptistHospitalinGaza.aspx?cms=q8FmFJgiscL2fwIzON1%2BDo%2Fd%2BrKo4CFNCvYRmJklLsI%3D; United Arab Emirates Ministry of Foreign Affairs, The UAE condemns the Israeli attack on Al-Ahli Baptist Hospital in Gaza and calls for an immediate cessation of hostilities, October 18, 2023, https://www.mofa.gov.ae/en/mediahub/news/2023/10/17/17-10-2023-uae-esrael.

7Héloïse Fayet, ‘The Evolving Role of Nuclear Rhetoric in Iran’s Strategic Calculus’, PRISME Initiative, 2025.