While the arms control community has largely focused on the implementation and effectiveness of multilateral arms embargoes, there is also merit in exploring unilateral restrictions on arms exports—i.e., those imposed by individual states. Such sanctions can be described as “national embargoes.” National embargoes, which range in scope and application, reflect the political objectives and concerns of the issuing state.

This article explores the national embargoes imposed against Türkiye following its invasion of northern Syria in 2019. These sanctions were implemented to force a change in Turkish foreign policy in the Middle East. States that announced embargoes generally reported reductions in arms export licences to Ankara the following year. Larger exporting states, all North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) allies of Türkiye, reported the most significant reductions in licensing values. A number of those states, alongside hopeful NATO members Sweden and Finland, would later end their embargoes after Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, when NATO enlargement and consolidation were perceived to be more important than subduing Turkish belligerence in the Middle East.

These findings, while not absolute, call into question the strategic and diplomatic benefit of national embargoes in influencing the policies and posturing of foreign states, particularly following wider geopolitical shocks. They also probe larger questions of the legitimacy in viewing arms sales, especially the throttling of arms sales, as instrumental in foreign policy generation.

Defining the “National Embargo”

An arms embargo restricts the transfer of military goods to a particular state or group. The broad intent is to influence the behaviour–historically, within the context of armed conflict or in response to serious human rights violation–of the sanctioned actor.1 A national arms embargo can be defined as one that is unilaterally and voluntarily applied by one state against another. Each embargo’s particular scope, application, and lifecycle are the products of the distinct considerations of the issuing state, providing insights into the active political calculations driving such sanctions.

A national arms embargo is wholly different from one enacted by multilateral bodies. A mandatory United Nations (UN) arms embargo imposed by the Security Council is the strongest and broadest example of this mechanism, with violations constituting a breach of the UN Charter.2

While arms embargoes by multilateral bodies are typically imposed in response to the outbreak of armed conflict or serious human rights violations, national embargoes can be imposed for political or strategic reasons, such as attempting to influence the actions of another state or blocking an adversary’s opportunities for procurement. While the phrase “embargo” suggests a comprehensive and complete sanctioning, national embargoes, as explored below, vary considerably in extent and application, and can largely be applied or lifted at will.

National embargoes have long been viewed as a foreign policy instrument by major arms exporting states. For example, the United States, far and away the largest weapons exporter, currently imposes restrictions on arms transfers to numerous states through the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) control regime.3

National embargoes may sometimes clash with established licensing procedures under certain existing arms control regimes. For example, except in circumstances in which a mandatory multilateral arms embargo applies, the Arms Trade Treaty4 and the European Union (EU) Common Position5 both determine the potential risks associated with arms transfers on a case-by-case basis—a process undermined by the blanket application of a national embargo.6

Operation Peace Spring

In October 2019, Türkiye launched Operation Peace Spring, a major land invasion of northeastern Syria and Türkiye’s third incursion into Syrian territory since 2016.

These operations aimed to degrade the capacity of the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) that were active in the region and prevent the consolidation of a nascent Kurdish state in this part of Syria. Türkiye targeted the YPG because of its reputed ties with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which has been engaged in a civil war against the Turkish government since the late 1970s.

Operation Peace Spring exacerbated existing tensions between Türkiye and western allies that had been spurred, in-part, by Türkiye’s acquisition of Russian-made S-400 missile systems, its aggressive posturing in the Mediterranean, and the increasingly autocratic policies of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s government.7 The invasion was immediately criticized by fellow NATO member states and the EU. A briefing published by the European Parliament described Operation Peace Spring as an indicator of the “further decoupling” between Türkiye and the United States and EU, showing how Türkiye’s strategic interests in Syria were at odds with those of the West.8

The EU and the United States designate the PKK, but not the YPG, as a terrorist group. Since 2015, several NATO member states had been providing security assistance to the YPG, which functioned as a regional ally in anti-ISIS operations and a thorn in the side of the weakened Syrian government.9 President Erdoğan viewed such assistance, which included military aid in the form of conventional arms transfers, as the arming of terrorists.10

Embargoes Begin

In the days immediately following the launch of Operation Peace Spring, several European states announced greater restrictions on arms exports to Türkiye. These embargoes served to advance two broad objectives: first, to send a strong signal of disapproval of Türkiye’s unilateral actions in the region; and second, to coerce a change in Türkiye’s hawkish foreign policy.

France and Germany, western Europe’s first- and second-largest arms exporters,11 almost immediately announced greater restrictions on arms exports to Türkiye.12 They were soon joined by Belgium,13 Czechia, Finland, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.14 EU member states collectively agreed to “commit to strong national positions regarding their arms export policy to [Türkiye]” but stopped short of imposing a formal EU-wide arms embargo.15

The scope of the national embargoes implemented in October 2019 varied widely. Czechia,16 Sweden,17 and Flanders18 immediately revoked existing export licences for military goods to Türkiye and refused to issue new ones. Finland,19 Norway,20 and Canada21 stated that they would not approve new export licences, while the Netherlands22 refused to issue new licences for either military goods or dual-use goods. Spain23 and the United Kingdom24 denied the authorization of new export licences for military goods broadly defined that could be used by Türkiye in Syria.

The United States had increased restrictions on the export of military goods to Türkiye following Türkiye’s 2017 deal to procure Russian-made S-400 missile systems.25 Following the failed Turkish coup d’état in 2016, Austria,26 Walloon,27 and Belgium28 had implemented embargoes, which remained unchanged following Operation Peace Spring.

Embargoes in Practice

The following section will analyze the value of arms export licences authorized29 by European states before and following Operation Peace Spring. Data was collected from the European External Action Service’s (EEAS) Conventional Arms Exports (COARM) public database.30

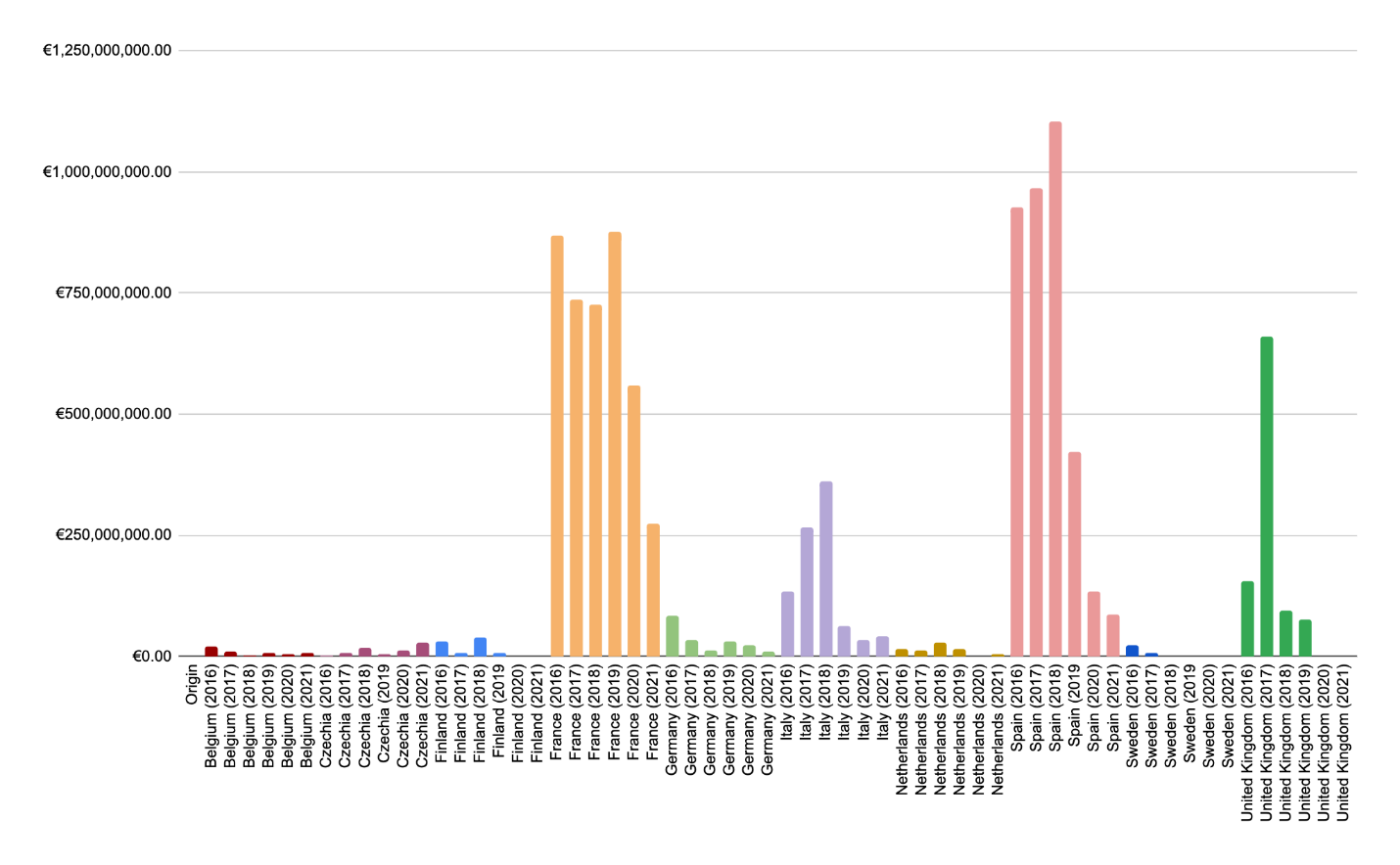

Nearly all states that announced stricter controls on the export of military goods to Türkiye in 2019 reported a reduction in the value of licence authorizations to that country the following year. States that had previously authorized large values in licences to Türkiye were both more likely to announce stricter controls and to report larger reductions in the value of licences post-2019.

Fig. 1: Annual Value of European Arms Export Licences to Türkiye (2016-2021)

Fig. 1: Reported values of European states that announced greater controls on arms transfers to Türkiye following Operation Peace Spring (October 2019). Source: EEAS COARM Database (Note: The data published by COARM is presented as annual totals. Therefore, embargoes that were implemented for only a series of months, or for a period greater than twelve months that otherwise extended across two calendar years, would not be reflected as such in the dataset.)

Fig. 1: Reported values of European states that announced greater controls on arms transfers to Türkiye following Operation Peace Spring (October 2019). Source: EEAS COARM Database (Note: The data published by COARM is presented as annual totals. Therefore, embargoes that were implemented for only a series of months, or for a period greater than twelve months that otherwise extended across two calendar years, would not be reflected as such in the dataset.)

The only state that did not conform to this pattern was Czechia. Despite an initially firm position by Czechia announced in October 2019, in 2020, the value of Czechia’s licence authorizations increased by approximately 250 per cent, from €3,784,940 in 2019 to €13,271,278 in 2020. The value of licences authorized by Czechia to Türkiye in 2021 increased by approximately 121 per cent over 2020 values to €29,360,268.

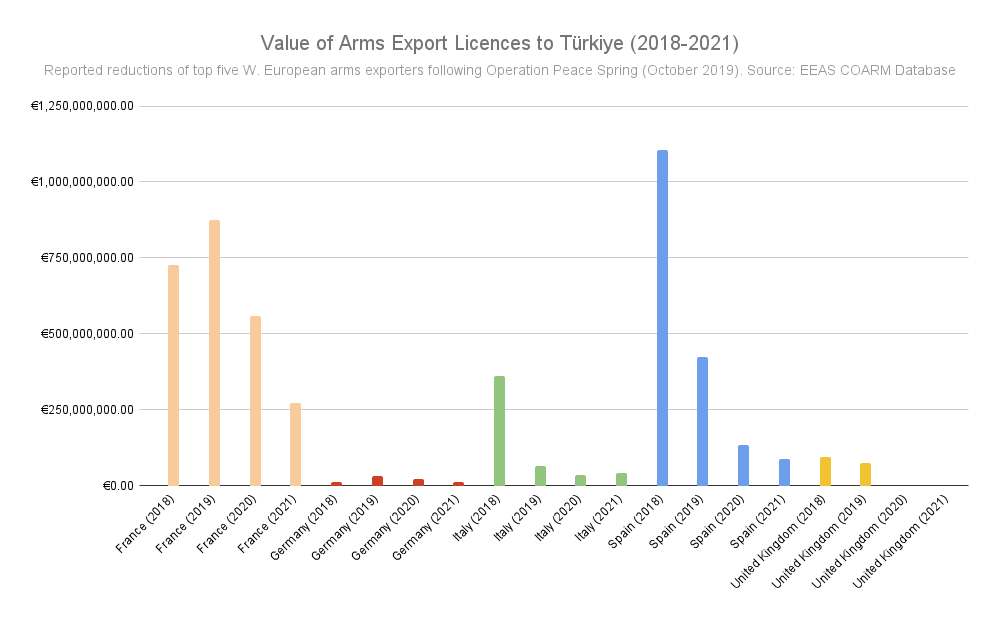

The five largest European arms exporters—the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Spain, and Italy—all observed reductions in licence values to Türkiye from 2019 to 2020. Italy aside, the value of licences for this group continued to trend downward in 2021.

Fig. 2: Annual Value of Arms Export Licences to Türkiye by Largest European Exporters (2018-2021)

Fig. 2: Reported reductions in the value of arms export licences to Türkiye by the top five Western European arms exporters following Operation Peace Spring (October 2019). Source: EEAS COARM Database

Of those states that implemented national embargoes following Operation Peace Spring, only Sweden, Finland, and the United Kingdom announced a complete suspension in licensing arms to Türkiye, listing nil values in 2020. Moreover, Sweden reported €0 in licence authorizations to Türkiye for the entirety of 2019, although its public announcement of greater controls was not made until October of that year.

Given the ebb and flow of the global arms market, it isn’t possible to say with certainty that the announcement of national embargoes directly led to a drop in licence authorizations in all instances. Contract awards could simply have been down for a given year, Türkiye could have contracted with other suppliers, or greater controls might have already been in place by October 2019 (and later strengthened or expanded following Operation Peace Spring).

For example, Sweden and Italy had already reported significant reductions in licence authorizations to Türkiye by 2019. In Germany’s case, the rate at which licence values fell in 2020 and then in 2021 resembled the annual rate of fluctuation in the two years prior to Operation Peace Spring. Nonetheless, all three states publicly declared greater restrictions on arms exports to Türkiye in October 2019.

Bulgaria, Croatia, Denmark, Lithuania, and Romania did not announce national embargoes and reported increases in licence values in the year immediately following Operation Peace Spring. These increases were generally not sizeable. Only Bulgaria, Denmark, and Romania saw increases valued at more than €5,000,000.31 The remaining European states that did not announce national embargoes saw either small (but arguably trivial) decreases in the value of licence authorizations to Türkiye in 2020 or had not reported any licence authorizations to Türkiye either before or after Operation Peace Spring.

In conclusion, large exporters were more likely to take a national position on arming Türkiye, and those exporters were more likely to see significant reductions in the value of licence authorizations in the year following Operation Peace Spring. This perhaps isn’t surprising, as those with ‘skin in the game’ could perceive themselves as better positioned to influence Türkiye more effectively by restricting the flow of arms.

Most states that reported reductions in licence values in 2020 saw modest increases in 2021. A number would soon altogether end their embargoes of Türkiye, some as a direct response to Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

The Effect of the 2022 Invasion of Ukraine on National Arms Embargoes

While Türkiye has been largely resolute in its support of Ukraine since the 2022 Russian invasion, it has used the conflict as an opportunity to situate itself as a mediator between Russia and the West and in so doing extract maximum strategic benefit.32 One benefit it demanded was an end to the national arms embargoes under discussion.33

Following Russia’s invasion, Sweden and Finland, both historically nonaligned countries, signaled their intention to join NATO. NATO membership is open to any state “in a position to further the principles of [the] Treaty and to contribute to the security of the North Atlantic area”; however, all current members of NATO must agree to a state’s accession.34

Türkiye immediately objected to membership for either country. It claimed that both Sweden and Finland were harbouring members of the PKK and requested their extradition. Türkiye also demanded that both states end their national arms embargoes and stop providing arms to Kurdish militant groups active in northern Syria.35

The invasion of Ukraine and subsequent geopolitical shifts have provided Türkiye newfound leverage against both Nordic states and NATO as a whole. At the same time, following the dramatic shift in continental security after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Sweden’s and Finland’s perceived benefits in maintaining national embargoes against Ankara have evidently shifted.

In spring 2022, Türkiye announced that it had begun meetings with Sweden and Finland to discuss reversals of their national embargoes.36 In September, Sweden announced that it had officially reversed its position and resumed licensing arms exports to Türkiye. In January 2023, Finland announced that it, too, had removed restrictions on licensing weapons to Türkiye.37 In both cases, it was widely reported that the dissolution of standing national arms embargoes was explicitly seen as a prerequisite for entry into NATO.38

It is worth noting that, until the 2022 invasion, both Sweden and Finland had among the most stringent national embargoes in place against Türkiye, as two of only three European states that reported a complete suspension in arms export authorizations. In the case of Sweden, this included a complete end to transfers.

The transactional nature of these policy reversals is obvious. Unlike mandatory multilateral embargoes, national embargoes can be both implemented and lifted when politically expedient, even when the stated goals of those sanctions—in this case, tempering Türkiye’s belligerence in Syria and beyond—have not been achieved. This belligerence was again on full display when Erdoğan threatened a fourth invasion of Syria to target Kurdish groups previously allied with several NATO states, under the pretext of a response to the bombing of İstiklal Avenue in Istanbul in November 2022.39

Responses of Other NATO Members

While most media attention was focused on the Swedish and Finnish embargoes, neither state was a major military supplier to Türkiye. As a result, the dissolution of those embargoes is unlikely to have a strong material effect. Türkiye was likely using its veto to achieve the dissolution of the existing embargoes of major suppliers, thereby “reset[ting] procurement ties with the West”; mending this relationship was of particular concern after Türkiye’s firm support for Ukraine made Turkish procurement from Russian manufacturers no longer possible.40

At the March 2022 NATO summit, President Erdoğan urged all member states to shutter any existing embargoes, stating that it was in the “common interest to remove the restrictions placed on our defense industry by some of our allies.”41

Europe’s five largest arms exporters, all NATO member states, had implemented national embargoes against Türkiye following Operation Peace Spring. Soon after the February 2022 invasion of Ukraine by Russia, three signaled the reversal of such restrictions.

Immediately after March 2022’s NATO summit, Italy and France effectively ended their respective arms embargoes when they announced that negotiations would resume to provide Türkiye with the SAMP/T air defence system co-produced by Italy and France. The original deal, signed in 2018, had been frozen by the implementation of national embargoes.42

Germany had imposed an embargo on the transfer of goods and components that could be used in ground operations after the onset of Operation Peace Spring.43 In June 2022, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz was asked if Germany would lift its arms embargo on Türkiye; he replied that “no such embargo existed”—a stark reversal of Germany’s previously reported position.44

Türkiye’s end goal may be to loosen the American embargo, which has likely had the greatest effect. U.S. sanctions have directly prevented Türkiye from acquiring new fighter jets—namely, the F-35—from American suppliers and upgrades to the Turkish fleet of F-16s. The Congressional Research Service has recently reported that Turkish procurement related to its F-16 program likely hinges on the admission of Sweden and Finland into NATO.45

Early Adopters

Unlike Italy, France, and Germany, NATO members the United Kingdom and Spain had ended their embargoes in the months prior to Russia’s invasion.

In December 2021, the United Kingdom again began to accept licence applications to export military goods to Türkiye; however, this position was only publicly announced following the March 2022 NATO summit at which Erdoğan urged an end to Western embargoes.46 Later in 2022, it was announced that Türkiye was looking to procure military goods worth more than US$10 billion from British suppliers, including Eurofighter Typhoons.47

Spain publicly ended its national embargo in November 2021, following a meeting between Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez and President Erdoğan, at which it was also announced that the two countries were to proceed with joint defence contracts.48

The Influence of Geopolitical Shifts on National Arms Embargoes

Except for Sweden and Finland, all states that announced national arms embargoes against Türkiye following Operation Peace Spring were NATO members. The original rationale for those sanctions—signaling disapproval of Türkiye’s intervention in Syria, and tempering Türkiye’s belligerent foreign policy in Syria and the wider region—has become secondary to the prospect of Sweden’s and Finland’s NATO membership. In an apparent quid pro quo, some of the largest arms exporters in NATO seem willing to reverse their national arms embargoes against Türkiye in exchange for Turkish support of NATO membership for Sweden and Finland.

The quick introduction and later reversal of these embargoes suggest their susceptibility to political shifts. There was little perceived change in Türkiye’s foreign policy towards Syria in the period directly before and following the implementation of such sanctions.

Much can be said about other factors at play in maintaining or reversing such national arms embargoes.49 There is also an obvious and important broader conversation to be had on the actual material extent of—and adherence to—these unilateral mechanisms.

Arms transfer authorizations must be conditioned on a potential recipient’s respect for human rights and international law—but such conditionality must also be absolute in measure and enforcement, with the end goal of protecting peace and security and reducing human suffering. Restricting arms sales to influence another state’s domestic or foreign policy, however, upholds the shaky assertion that arms sales themselves are a primary tool of influence, a notion further problematized in the case of Türkiye.

1Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), “Arms Embargoes,” 2023 https://www.sipri.org/databases/embargoes.

2Brian Wood, “Strengthening Compliance with UN Arms Embargoes – Key Challenges for Monitoring and Verification,” Amnesty International, 2006, https://www.amnesty.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/ior400052006en.pdf. Examples of other multilateral bodies that implement arms embargoes include the European Union, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, and the Economic Community of West African States.

3University of Pittsburgh Office of Trade Compliance, “Embargoed and Sanctioned Countries,” 2023, https://www.export.pitt.edu/embargoed-and-sanctioned-countries.

4The text of the Treaty does not explicitly use the term “case-by-case”; however, the relevant article (Article 7, “Export and export assessment”) has been interpreted as requiring a case-by-case assessment. For example, see Delegation of the European Union to the UN and other international organisations in Geneva, Arms Trade Treaty – Working Group on Effective Treaty Implementation – Sub-working Groups on Articles 6&7 and Article 9 (joint meeting) – EU Statement, February 16, 2023, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/delegations/un-geneva/arms-trade-treaty-working-group-effective-treaty-implementation-sub-working_en?s=62.

5European Union, Council Common Position 2008/944/CFSP, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:32008E0944.

6For these reasons, states do not refer to such practice as a “national embargo” and instead may refer to the practice of an “assumption of denial” against a certain state when conducting risk assessment on potential arms transfers.

7Christopher Woody, “The US Dispute with Turkey over Russian Weapons Could Mean More Problems on NATO’s ‘Most Troublesome’ Front,” Insider, November 20, 2019, https://www.businessinsider.com/us-turkey-russian-s400-tension-could-be-problem-black-sea-2019-11.

8European Parliament, Turkey’s Military Operation in Syria and its Impact on Relations with the EU, Briefing, 2019, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/EPRS/EPRS-Briefing-642284-Turkeys-military-operation-Syria-FINAL.pdf.

9Megan A. Stewart, “What’s at Stake if Turkey Invades Syria, Again,” Middle East Institute, December 7, 2022, https://www.mei.edu/publications/whats-stake-if-turkey-invades-syria-again.

10BBC News, “Syria Conflict: US Sends Arms to Kurdish Forces Fighting IS,” May 30, 2017, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-40100917.

11SIPRI, Trends in International Arms Transfers, 2022, SIPRI Fact Sheet, March 2023, https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2023-03/2303_at_fact_sheet_2022_v2.pdf.

12The Times of Israel, “France, Germany Halt Arms Exports to Turkey as Arab League Demands UN Action,” October 12, 2019, https://www.timesofisrael.com/france-germany-curb-arms-exports-to-turkey-as-arab-league-demands-un-action.

13Robin Emmott, “EU Governments Limit Arms Sales to Turkey but Avoid Embargo,” Reuters, October 14, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-syria-security-eu-france-idUSKBN1WT0M4.

14Reality Check team, “Turkey: Which Countries Export Arms to Turkey?” BBC News, October 23, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/50125405; and AFP, “NATO Ally Norway Suspends New Arms Exports to Turkey,” Al Alarabiya News, October 10, 2019, https://english.alarabiya.net/News/middle-east/2019/10/10/NATO-ally-Norway-suspends-new-arms-exports-to-Turkey.

15Emmott, see Note 13.

16Daniela Lazarová, “Czech Republic Suspends Weapons Exports to Turkey,” Radio Prague International, October 15, 2019, https://english.radio.cz/czech-republic-suspends-weapons-exports-turkey-8118143.

17Sveriges Radio, “Sweden Stops Military Exports to Turkey,” October 16, 2019, https://sverigesradio.se/artikel/7322488.

18This policy also extended to dual-use goods. Email correspondence with Dr. Diederik Cops, March 2023.

19Yle News, “Finnish Arms Exports to Turkey Have Grown Quickly,” October 10, 2019, https://yle.fi/a/3-11015100.

20AFP, see note 14.

21Global Affairs Canada, Government of Canada, 2019 Exports of Military Goods, modified June 23, 2022, https://www.international.gc.ca/trade-commerce/controls-controles/reports-rapports/military-goods-2019-marchandises-militaries.aspx?lang=eng#_Toc38893611.

22Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Government of the Netherlands, “Change of National Export Control Policy with regard to Turkey following the Turkish Army’s Incursion into Northern Syria,” October 15, 2021, https://www.government.nl/documents/publications/2021/10/15/change-of-national-export-control-policy-with-regard-to-turkey-following-the-turkish-armys-incursion-into-northern-syria.

23AFP, “Spain Stops Arms Exports to Turkey over Syria Offensive,” Al Alarabiya News, October 15, 2019, https://english.alarabiya.net/News/middle-east/2019/10/15/Spain-stops-arms-exports-to-Turkey-over-Syria-offensive.

24Financial Times, “UK Suspends All New Arms Sales to Turkey,” October 15, 2019, https://www.ft.com/content/bde7fa7e-eebb-11e9-ad1e-4367d8281195.

25Amanda Macias, “U.S. Sanctions Turkey over Purchase of Russian S-400 Missile System,” CNBC, December 14, 2020, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/12/14/us-sanctions-turkey-over-russian-s400.html.

26Rudaw, “Austria Votes to Impose Arms Embargo on Turkey,” November 24, 2016, https://www.rudaw.net/english/middleeast/turkey/241120163.

27Observatoire des armes wallonnes, “Rapport de l’observatoire des armes wallonnes, 3ème édition,” May 26th, 2020, p. 7, https://www.liguedh.be/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/observatoire_des_armes_wallonnes_-_3e_me_e_dition.pdf.

28Email correspondence with Dr. Diederik Cops, March 2023.

29Many practitioners argue that data on actual transfers is superior to data on licence authorizations. However, licensing data can provide a more comprehensive look at the material effect of relatively short-lived national embargoes. This is because states are more likely to refuse approval of future exports than to renege on those already authorized for transfer. This was generally the case observed in sanctions against Türkiye.

30The EEAS COARM database is populated with the data that is submitted annually by states. The database publishes data on actual transfers as well as licence authorizations, but not all states submit data on actual transfers. Therefore, this memo relies only on the value of licence authorizations. This analysis does not assess the veracity of data submitted by individual states. The database can be accessed here: https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/eeasqap/sense/app/75fd8e6e-68ac-42dd-a078-f616633118bb/sheet/74299ecd-7a90-4b89-a509-92c9b96b86ba/state/analysis.

31Of these states, Bulgaria saw the largest increase at €93,065,625 over 2019’s value of licence authorizations.

32Iliya Kusa, “Turkey’s Goals in the Russia-Ukraine War,” Wilson Center, June 13, 2022, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/turkeys-goals-russia-ukraine-war.

33Selcan Hacaoglu, “Erdogan Urges NATO Allies to End Arms Embargoes on Turkey”, Bloomberg, March 24, 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-03-24/erdogan-urges-nato-allies-to-end-arms-embargoes-on-turkey?leadSource=uverify%20wall.

34NATO, NATO Enlargement & Open Door, Fact Sheet, July 2016, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/pdf_2016_07/20160627_1607-factsheet-enlargement-eng.pdf.

35Ibid.

36Reuters, “Turkey Observed Positive Approach to Lifting Arms Embargo from Finland, Sweden – Erdogan Spokesman,” May 25, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/turkey-observed-positive-approach-lifting-arms-embargo-finland-sweden-erdogan-2022-05-25.

37Ezgi Akin, “Finland Lifts Turkey’s Arms Embargo, Is One Step Closer to NATO,” Al-Monitor, January 25, 2023, https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2023/01/finland-lifts-turkeys-arms-embargo-one-step-closer-nato.

38For example, see Al Jazeera, “Why Did Turkey Lift its Veto on Finland and Sweden Joining NATO?” June 29, 2022, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/6/29/why-did-turkey-lift-its-veto-on-finland-sweden-joining-nato-explainer; Yaroslav Lukov and Matt Murphy, “Turkey Threatens to Block Finland and Sweden Nato Bids,” BBC News, May 17, 2022, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-61472021; and Gerard O’Dwyer, “Turkey Frustrates Finland’s and Sweden’s NATO Bids,” Defense News, January 30, 2023, https://www.defensenews.com/global/europe/2023/01/30/turkey-frustrates-finlands-and-swedens-nato-bids.

39Stewart, see Note 9.

40Burak Ege Bekdil, “Turkey Seeks to Repair Ties with Western Procurement Club,” Defense News, June 6, 2022, https://www.defensenews.com/global/europe/2022/06/06/turkey-seeks-to-repair-ties-with-western-procurement-club.

41Hacaoglu, see Note 33.

42Tayfun Ozberk, “Turkey and Italy Hint at Return to SAMP/T Air Defense Efforts,” Defense News, April 1, 2022, https://www.defensenews.com/industry/techwatch/2022/04/01/turkey-and-italy-hint-at-return-to-sampt-air-defense-efforts.

43Duvar English, “Turkey Facing Informal Arms Embargo from Germany: Defense Minister”, Duvar English, September 15, 2021, https://www.duvarenglish.com/turkey-facing-informal-arms-embargo-from-germany-defense-minister-hulusi-akar-news-58836.

44Turkish Minute, “There’s No Arms Embargo on Turkey, Germany’s Scholz Says,” June 29, 2022, https://www.turkishminute.com/2022/06/29/heres-no-arms-embargo-on-turkey-germanys-scholz-says.

45Jim Zanotti, Clayton Thomas, Turkey (Türkiye): Major Issues and U.S. Relations, Congressional Research Service, March 31, 2023, p. 18, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R44000.

46Ragip Soylu, “UK lifts all restrictions on defence exports to Turkey”, Middle East Eye, May 20th, 2022, https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/uk-turkey-defence-exports-restrictions-lifted

47Ragip Soylu, “Turkey exploring massive UK arms deal involving planes, ships, and tank engines”, Middle East Eye, January 20th, 2023, https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/turkey-uk-massive-arms-deal-planes-ships-tank-engines

48Sarantis Michalopoulos, “Greece fumes over new Spain-Turkey armament deal”, EURACTIV, November 19, 2021, https://www.euractiv.com/section/defence-and-security/news/greece-fumes-over-new-spain-turkey-armament-deal/

49This analysis largely relied upon public statements issued by governments to determine which regions and states had maintained or reversed national arms embargoes in the period following the February 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. However, the largely ‘informal’ nature of many national embargoes means that their status can change without any public statement from the issuing government (as demonstrated in the case of the United Kingdom), let alone an update to or written amendment of respective national arms control policies. Updated data on national arms export licensing to Türkiye from the EEAS COARM database will provide more concrete insights into the status of those embargoes and allow fuller analysis on the influence of the Russian invasion on Western sanctioning of Turkish arms transfers.