The Middle East, and specifically the Gulf states, are the UK’s biggest arms export market. This paper argues that the UK arms industry’s dependence upon Gulf arms exports, along with the UK’s strategy of closely aligning its foreign and defence policy with the US, locks in a highly militarised relationship with the region in which the arms trade plays a central role. For the UK to change course and decentre the arms trade in its relationship with the region would not only require fundamental shifts in the UK’s global outlook but would be much more likely in concert with a similar US shift away from a militarist approach to the Middle East.

The UK has a long history of military and political involvement in the Middle East, especially since World War I, with its “Mandates” in Palestine, Jordan and Iraq, colonial rule or “protectorates” in Egypt, Yemen, Bahrain, and the UAE, and critical support for the rise of the House of Saud. The UK continues to have particularly close political, economic, military, and personal links, including royal-to-royal connections, with the absolute monarchies of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC).1 Even in Oman, where the UK has no past colonial relationship, the ruling family has surrounded itself with prominent advisers from the UK ruling establishment.2

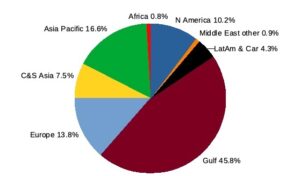

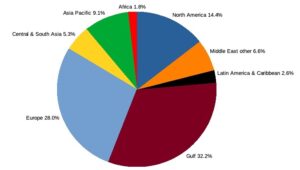

The Middle East, specifically the Gulf, is by far the dominant market for UK arms outside its US and European allies. From 2004-2023, 36% of UK exports of major conventional weapons were to the GCC states, while 27.6% was to NATO allies (see figure 1).3 Export licensing data on the value of ‘single’ licences, which includes a much wider range of equipment, tells a similar story,4 where Saudi Arabia, Oman, Qatar, and to a lesser extent the UAE, are the dominant recipients in the region (see figure 2).5

Figure 1: UK deliveries of major conventional weapons by region, 2014-2023

Source: SIPRI Arms Transfers Database

Figure 2: Value of UK Single Individual Export Licences for military goods by recipient region 2014-2023

Source: UK Government, Strategic Export Controls: licensing data

The Gulf states are particularly important for UK exports of combat aircraft, currently the Eurofighter Typhoon, for which they have been the only customers in recent years. Elsewhere, the Eurofighter has been outcompeted by aircraft from the US, Russia, and France.

Saudi Arabia in particular is seen as vital for maintaining the UK’s combat aircraft production and technological capabilities, as domestic orders alone cannot sustain them. Starting from the Al Yamamah deals in the 1980s and 1990s, sales and ongoing maintenance of Tornado and Typhoon combat aircraft, Hawk trainers, and other equipment have generated £88 billion in revenue to BAE Systems up to 2023.6

UK arms sales to the rest of the Middle East are much smaller: just 2.2% of UK exports of major conventional weapons from 2004-2023 were to the rest of the MENA region, outside the Gulf.7Despite limited UK arms sales to the MENA region beyond the Gulf, the UK is heavily involved in the region, having taken a major role alongside the US in wars in Iraq, Libya, and Syria.

In general, UK policy in the Middle East is based on its broader geopolitical strategy of tying itself closely to the US, and the UK thus largely shares US interests and priorities, as well as the highly Orientalist, transactional, and militarised perspective the US applies to the region.8 These priorities include support for Israel, containing Iran, fighting Islamist terrorism, ensuring the stability of oil supplies, and regime stability. It should also be said that these priorities and this militarist lens are very much in keeping with the UK’s historical relationship with the Middle East.

Arms sales policy

The UK, under successive governments, has accorded a high priority to maintaining its arms trade with the Middle East, regardless of concerns about conflict or human rights, and sometimes even over more self-interested policy priorities. This can be seen in both the cases of Saudi Arabia and (with a far lower level of sales) Israel.

The UK has gone to great lengths to maintain its long-standing arms exports to Saudi Arabia, its top arms customer for the past 20 years. In 2006, the UK government cancelled a Serious Fraud Office Investigation into massive bribes paid to Saudi leaders by BAE Systems, worth up to £6 billion over the years, in connection with the Al Yamamah series of arms deals.9 This sparked outrage not just among civil society, but also among the UK’s economic partners and allies, and drew severe criticism from the OECD for violating the OECD Convention on Corruption.10 The UK’s international reputation for anti-corruption was severely damaged, but cancelling the investigation paved the way for the Al Salam deal in 2007 for the sale and ongoing support of Eurofighter Typhoons to Saudi Arabia, and thus ensured a steady stream of work for BAE’s combat aircraft production line.11

More recently, UK arms sales to Saudi Arabia continued unabated during the devastating Saudi-led war on Yemen, and after the 2018 murder of Jamal Khashoggi, while many European countries limited or halted transfers to the Saudi Coalition. When the Biden Administration halted the sale of precision-guided munitions to Saudi Arabia in 2021 (though maintaining the bulk of US arms supplies to the country),12 the UK did not follow suit, continuing with all arms sales including substantial supplies of air-to-surface missiles and guided bombs, marking a rare deviation from US policy.13

In the case of Israel, UK arms sales are mostly components, in many cases going via the US, as part of systems such as F-16 or F-35 combat aircraft, or Apache attack helicopters.14 Nonetheless, these components can be significant; for example, 15% of the value of each F-35 is produced in the UK.15

At times, some UK governments have shown an inclination toward a more restrictive arms export policy to Israel; for example, after Israel’s Operation Cast Lead in Gaza in winter 2008-09, the government carried out a review of what Israeli systems used in the conflict contained UK components, identifying several (including F-16s, Apaches, and corvettes) that almost certainly did, indicating that this would be taken into account in future licensing decisions.16 However, such tendencies have been subordinated to defence industrial interests, especially where they concern relations with the US.

In 2002, the UK had moved towards a policy of denying export licences for equipment likely to be used by Israel in the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPT). However, it faced a dilemma over supplying head-up/down display systems to the US for incorporation into F-16 destined for Israel. It chose to permit the exports by introducing an entirely new set of additional criteria relating to such ‘incorporation’ licences, allowing factors such as defence industrial interests and relationships with the incorporating country to be taken into account. Nonetheless, the government clearly admitted that direct exports of such equipment to Israel would not have been permitted.17

The new Labour government elected in July quickly announced a review of export licences to Israel amid the ongoing genocide in Gaza and an impending legal challenge. Despite its landslide election victory, Labour lost large numbers of voters, and several Parliamentary seats, to Green and left-wing independent candidates, with a particularly severe decline among Muslim voters. Moreover, it was increasingly hard to maintain the claim, based on government legal advice, that there was no ‘clear risk’ that UK-supplied equipment being used to commit serious violations of International Humanitarian Law (IHL) in Gaza, which according to the UK’s export licensing criteria should require a halt to export licences.18

On 2 September, the government announced the result of its review.19 It concluded that Israel was likely violating IHL in Gaza. It therefore announced that it was suspending around 30 export licences for military equipment for use in Gaza, including items such as components for combat aircraft, military helicopters, UAVs, and targeting equipment.

However, there was one major exemption to the suspension of equipment for use in Gaza: the supply of components for the F-35 aircraft to Israel was permitted to continue, provided the components were not supplied directly, i.e. through a third country, primarily the USA. Israel is using the F-35s extensively in the Gaza war, alongside its F-15s and F-16s. Spare parts are needed in large quantities for such operations, and the US has rushed them to Israel for the F-35 “at breakneck speed”.20 Based on the unit cost of the F-35 and the UK’s 15% share, the F-35 components are almost certainly the largest and most significant aspect of the UK’s arms sales to Israel.

The government justified the F-35 exemption on the grounds that halting the supply of components to Israel would disrupt the entire F-35 global supply chain, involving many partner nations.21 In exempting the F-35, it did not try to claim that there was no risk of the planes, including their UK-supplied components, being used in IHL violations.22 Instead, it announced that it was applying essentially an ad-hoc exception to the regular export licensing criteria, allowing itself to break its own rules. The legality of this manoeuvre is likely to be tested in court.

The real reason for this exception is almost certainly political. Refusing to supply components for Israeli F-35s would undoubtedly anger the US and risk negative consequences for the UK’s role in the F-35 programme. It was for this reason that I predicted in the preliminary version of this memo that the government would try to find a way to keep the F-35 components flowing. Although the UK’s arms trade with Israel, even including the share of the F-35s, is relatively small, the overall value of the F-35 programme to the UK arms industry is substantial, with BAE Systems alone receiving over £2 billion in revenue from the programme in 2023, including over £1 billion for its UK operations.23

While both cases show a consistent tendency to support the interests of the arms industry, there is an important difference: with Saudi Arabia, the arms sales themselves are the primary driver due to their crucial role in sustaining the UK’s combat aircraft production capabilities, while in the case of Israel, it is the relationship with the US, and specifically defence industrial ties, that looms largest.

In this way, the twin drivers of UK policy towards the Middle East become evident: arms exports in the Gulf, and alignment with US policy in the rest of the region. Between them, they cement the UK’s highly militaristic approach to the region, and its unwillingness to stem arms exports. Moreover, these motivations will only have become stronger in recent years as the geopolitical environment has worsened. The Russian invasion of Ukraine, coupled with a growing belief within the UK security establishment that all-out war with Russia is a genuine prospect, has only heightened the UK’s desire to remain at the forefront of global arms production, and to cleave even more closely to the US as a guarantee of security.

Prospects for reorienting policy

In the face of these powerful drivers – the desire to sustain a strong UK defence industrial base capable of producing cutting-edge platforms, and the UK’s long-standing strategy of closely aligning with US policy to maintain its relevance as a military and geopolitical power – identifying pathways for the UK to decentre the arms trade and move away from its militaristic approach to the Middle East presents a significant challenge.

Certainly, such a shift would be much easier if carried out alongside a similar change by the US, as many participants in this project have argued for.24 Both the US and the UK have prioritised military force as the go-to means for addressing regional issues, be that terrorism, opposition to entrenched and corrupt authoritarian regimes, Palestinian aspirations for freedom and statehood, or the civil wars in Libya and Yemen. This is not simply a case of the UK following the US against its better judgement; Tony Blair was just as enthusiastic about the invasion of Iraq as George W. Bush, and the UK was more gung-ho about intervention in Libya than the Obama administration. The UK elite’s view of the Middle East as a region characterised by irrational hatreds and threats that require management by strong local autocrats and/or direct military intervention is long-standing.25 However, the failures of this approach have also long been apparent, and a combined shift by the US and the UK towards prioritising diplomacy and political solutions would be more likely to bear fruit than the UK attempting this alone.

Breaking from the militaristic and arms trade-centric relationship with the Gulf would require an even more fundamental reassessment of the UK’s place in the world, and a deprioritising of defence industrial interests, specifically those of BAE Systems. As my recent report on the influence of the UK arms industry on government argues,26 the UK arms industry has developed such a close institutional relationship with government that the boundaries between the two have become blurred, if not erased. BAE Systems, for example, has had more meetings with ministers, and more with prime ministers, from 2012 to 2023, than any other private company. Ending or even significantly reducing the arms trade with Saudi Arabia would mean a severe hit to BAE’s profits, and would call into question the UK’s ability to maintain its combat aircraft production capability. This would entail either greater dependence on US imports such as the F-35 (in which, as noted, BAE and the UK arms industry have a substantial stake), significantly increased spending to maintain capabilities without Gulf exports, or accepting a diminished position in the global military hierarchy.

A more modest step could involve a greater willingness to use the supposed leverage provided by arms sales to influence Gulf customer behaviour and promote political and diplomatic solutions to conflicts such as the Yemen war. Without completely ending UK support for the Saudi Air Force, the government could have restricted the flow of munitions or delayed the final batch of Eurofighters in 2017 to push for a less warlike approach to Yemen. Instead, they chose to continue arms supplies, despite the horrific humanitarian consequences and the patent failure of the Saudi-led war to achieve its goals. Such an approach would be imperfect – as Nancy Okail points out in her paper in this series,27 using the leverage of arms sales still centres the arms trade in western-Middle East relationships, but it would be a step forward from unconditional support for arms exports regardless of the consequences.

In the longer-term, the UK should move away from its imperialist and Orientalist view of the region,28 as being somehow ‘culturally’ averse to democracy and human rights, and requiring ‘enlightened’ monarchs, supported by the west to guide its ‘backward’ people towards modernity. This view ignores the many genuine, though currently suppressed, voices for democracy and human rights within the region, excuses egregious human rights abuses by supposedly enlightened rulers, and bets implausibly on the indefinite survival of autocratic regimes in the face of the demands of their people. A good starting point might be to actually engage with civil society actors in the region, and in diaspora communities, who could provide alternative perspectives on their countries’ security concerns beyond those of the ruling elite. Unfortunately, there has been no indication so far from any past or likely future UK government of a willingness to challenge the current approach.

1See e.g. David Wearing, Anglo Arabia: Why Gulf wealth matters to Britain, Polity, 2018.

2Phil Miller, “‘Colonialism never ended’: The elite British cabal propping up a Gulf dictatorship”, Daily Maverick, 20 April 2021, https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-04-20-colonialism-never-ended-the-elite-british-cabal-propping-up-a-gulf-dictatorship/

3SIPRI Arms Transfers Database, https://armstransfers.sipri.org/ArmsTransfer/

4Single Individual Export Licences (or SIELs) permit the export of a fixed quantity and value of equipment to a given destination and are the only type of UK export licence with a published value attached. However, roughly half of UK arms exports are made using ‘open’ licences which allow for unlimited deliveries and have no value attached. The value of deliveries using any type of export licence is not monitored. The value of the single licences is therefore of limited value as a guide to the full value of UK arms exports; however, unlike the more comprehensive data on the value of contracts, it is the only official data broken down by recipient.

5See e.g. Sam Perlo-Freeman, Annual Report on UK arms exports in 2022, Campaign Against Arms Trade, 5 October 2023, https://caat.org.uk/publications/annual-report-uk-arms-exports-in-2022/

6Then-BAE Chair Mike Turner is quoted as saying in August 2006 that the Al Yamamah deal had been worth £43 billion to the company over the previous 20 years; BAE Annual Reports for 2007 to 2023 show the company receiving a further £45 billion in revenue from the Saudi Ministry of Defence and Aviation since then. Defense Industry Daily, “Grand Salaam! Eurofighter Flies Off With Saudi Contract”, entries from November 2004 to 9 July 2014, accessed 31 July 2024, https://www.defenseindustrydaily.com/the-2006-saudi-shopping-spree-eurofighter-flying-off-with-10b-saudi-contract-updated-01669/.

7The share of single export licence value in the past 10 years is somewhat higher at 7.1%, but still far lower than to the Gulf, at 32.2%.

8As discussed by Waleed Hazbun, “The Spiral of Militarization in US Policy Towards the Middle East”, PRISME Initiative, Spring 2024, https://prismeinitiative.org/blog/spiral-of-militarization-us-policy-middle-east-waleed-hazbun/, in the third SALAM debate series.

9See e.g. Corruption Tracker, “Al Yamamah arms deal”, 18 April 2023, https://corruption-tracker.org/case/al-yamamah-arms-deals

10Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), United Kingdom: Phase 2bis. Report on the Application of the Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions and the 1997 Recommendation on Combating Bribery in International Business Transactions. Paris: OECD

11E.g. Al Jazeera, “Saudi Arabia ‘buys 72 Eurofighters’”, 17 September 2007, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2007/9/17/saudi-arabia-buys-72-eurofighters

12See https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/press-briefings/2021/02/04/press-briefing-by-press-secretary-jen-psaki-and-national-security-advisor-jake-sullivan-february-4-2021/. The Administration announced it would be halting the supply of “offensive weapons”, and was reviewing all arms sales, but the only clear stop was on precision-guided munitions. Maintenance of US-supplied Saudi equipment, logistics support, and sales of air-air missiles, Patriot air defence systems, surveillance aircraft, and more continued. The freeze on the sale of munitions was lifted in August 2024. https://www.state.gov/briefings/department-press-briefing-august-12-2024/#post-578484-SAUDIYEMEN.

13Dan Sabbagh, “UK authorised £1.4bn of arms sales to Saudi Arabia after exports resumed”, The Guardian, 9 Fen. 2021, https://amp.theguardian.com/world/2021/feb/09/uk-authorised-14bn-of-arms-sales-to-saudi-arabia-after-exports-resumed

14The highest value single licence to Israel was for £182 million, for “technology for military radars” in 2017, an unusually high sum for an intangible technology transfer. No information is available on the type of radar system involved. Other licences issued for direct export to Israel (i.e. not via the US or some other country) have been overwhelmingly for components.

15E.g. Shephard Media, “UK takes delivery of two new F-35B fighter jets”, 26 June 2023, https://www.shephardmedia.com/news/air-warfare/uk-takes-delivery-of-two-new-f-35b-fighter-jets/

16Hansard, Written Ministerial Statements, “Israel (UK Strategic Export Controls)”, Statement by the Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs (David Miliband), 21 April 2009, https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200809/cmhansrd/cm090421/wmstext/90421m0001.htm#090421109000043

17E.g. Anna Stavrianakis, “Missing in Action: UK arms export controls during war and armed conflict”, 1 March 2022, https://worldpeacefoundation.org/publication/missing-in-action-uk-arms-export-controls-during-war-and-armed-conflict/

18E.g. Imran Mulla, “Exclusive: UK expected to restrict arms sales to Israel and drop ICC objection”, Middle East Eye, 25 July 2024, https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/exclusive-uk-likely-restrict-arms-sales-israel-and-drop-icc-objection. The UK’s export licensing criteria can be found at https://questions-statements.parliament.uk/written-statements/detail/2021-12-08/hcws449.

19https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-suspends-around-30-arms-export-licences-to-israel-for-use-in-gaza-over-international-humanitarian-law-concerns

20Michelle Fahy, “Australia and the F-35 supply chain: in lockstep with Lockheed”, Undue Influence blog, 3 May 2024, https://undueinfluence.substack.com/p/lockstep-with-lockheed-australia

21A dubious claim, given the comprehensive electronic stockpile management system used for the aircraft. For more discussion of this, see e.g. https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/israel-US-f-35-global-supply-legal-spare-parts

22A subsequent answer to a parliamentary question confirmed that this move was in fact a departure from the Strategic Export Licensing Criteria.

23BAE Systems Annual Report 2023.

24E.g. Elias Yousif, “The Fear of Missing Out – Reconsidering Assumptions in US Arms Transfers to the Middle East”, PRISME Initiative, Spring 2023, https://prismeinitiative.org/blog/fear-of-missing-out-elias-yousif/; Nancy Okail, “Rethinking Arms Transfers: Navigating the Complexities of U.S. Military Aid to the Middle East and Its Implications for Regional Stability and Human Rights”, PRISME Initiative, Spring 2023, https://prismeinitiative.org/blog/rethinking-arms-transfers-to-mena-nancy-okail/; Waleed Hazbun, “The Spiral of Militarization in US Policy Towards the Middle East”; and Jennifer Erickson, “US Arms Transfers to the Middle East: Challenges of Change”, PRISME Initiative, Autumn 2024.

25Wearing, Anglo-Arabia, and David Wearing, “The myth of the reforming monarch: Orientalism, racial capitalism, and UK support for the Arab Gulf monarchies”, Politics, Vol. 44 issue 3, August 2024, first published online 2 September 2021, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/02633957211041547

26Sam Perlo-Freeman, From revolving door to open-plan office: the ever-closer union between the UK government and the arms industry, World Peace Foundation/Campaign Against Arms Trade, 18 September 2024, https://caat.org.uk/publications/from-revolving-door-to-open-plan-office-the-ever-closer-union-between-the-uk-government-and-the-arms-industry/

27Nancy Okail, “Rethinking Arms Transfers”.

28As discussed in David Wearing, “The Myth of the Reforming Monarch”.