Author’s note 1

It is well known that conventional arms transfers have long played a major role in US policy toward the Middle East – and in US foreign policy in general.2 Since the Cold War, the US government has promoted arms transfers as a source of political, security, and economic benefits. At the same time, at least on paper, US arms export policy also frequently seeks to uphold commitments to human rights, stability, and peace. Rather than striking a functional balance, however, these goals often come into direct conflict in US Middle East policy, raising questions about the United States’ role as the top arms exporter to the region. The project of “decentering arms in Middle East security” must therefore attend not only to importer demand but also to drivers of supply in the United States and other major arms producers.3 This essay will address the latter, focusing on shared ideas in American politics about the value of arms exports in US foreign policy.

Scholars commonly point to entrenched interests in promoting ongoing arms sales4: the US defense industry relies on exports as a key component of its business model and frequently hires former military and government officials as lobbyists, advisors, and board members.5 The US government pursues arms deals abroad, citing support for the defense-industrial base and national economic benefits as core motivations to sell.6 In addition to these entrenched interests, however, this essay argues that three interlocking and deeply embedded ideas shape US participation in international arms markets: arms as a signal of support, arms as a source of influence, and the inevitability of alternative suppliers. These ideas are widely shared and promoted by government officials, defense industry representatives, and the popular media, and are institutionalized in US law and policy.

By overlooking these three ideas as themselves influential, I argue that experts and advocates miss a fundamental driver of US arms exports and a core challenge in “decentering arms.” Statements of facts and research findings alone have long proven insufficient to dislodge them. In the context of a re-emerging “Cold War,” they will only become harder to shake. Indeed, they will be enhanced, not diminished, by current developments in international security. If advocates wish to persuade policymakers to de-emphasize arms sales in US policy toward the Middle East, then they need to consider how to pursue broader ideational change.

Background on US arms sales

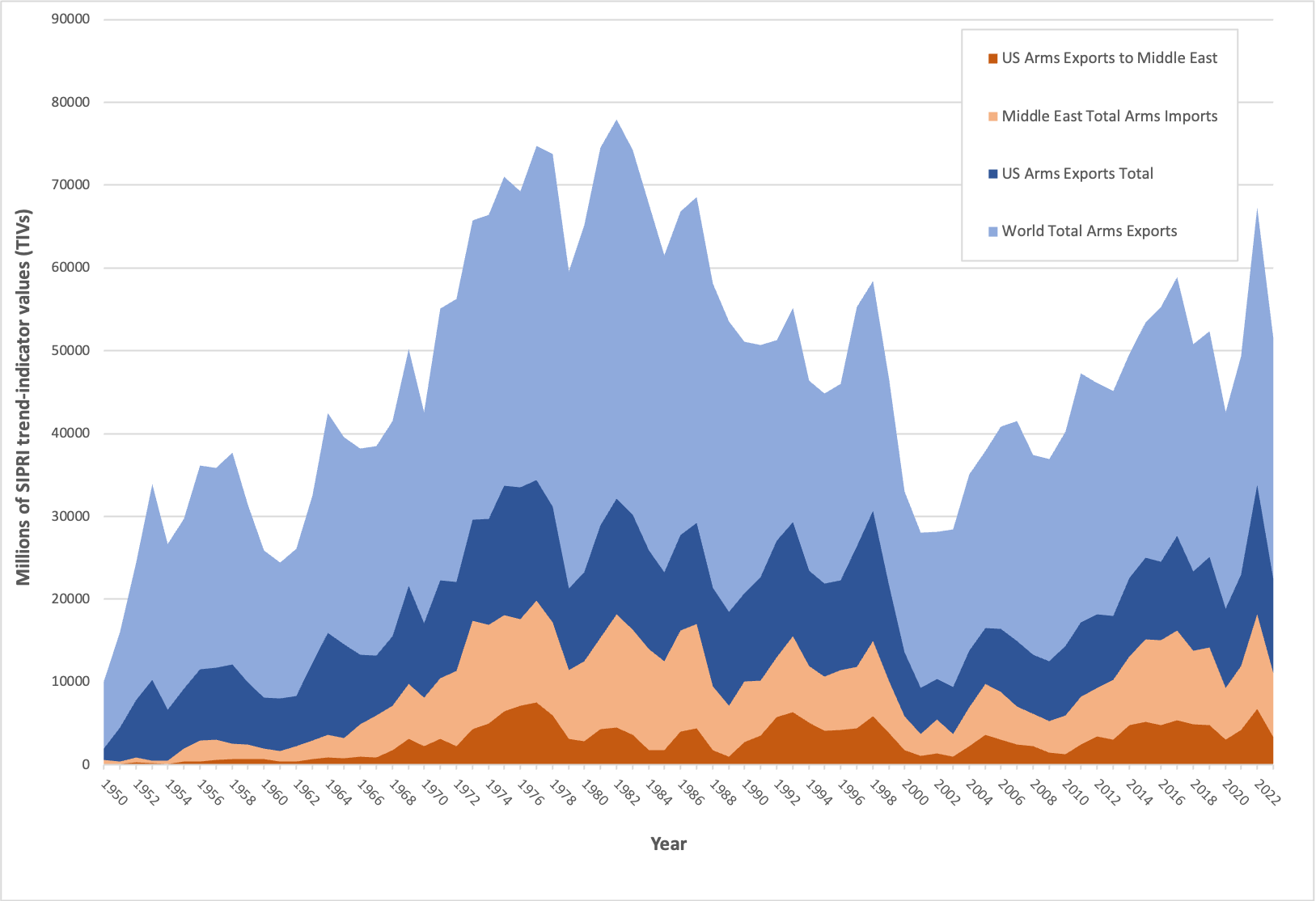

As a region, the Middle East is the top recipient of US arms sales, and the US is the top supplier of arms (see Figure 1). The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) reports that, from 2019-23, 38% of US arms exports went to countries in the Middle East.7 These countries made up the largest regional share of US arms exports in this period. Nevertheless, volume was down from 50% of US arms to the region in the 2014-18 period.8 The United States is by far the dominant arms supplier to the Middle East, accounting for 52% of regional imports in 2019-23 compared to 12% from France, the next largest supplier.9

Figure 1. Arms Transfers Trends, 1950-202310

In general, US arms export law is designed to promote arms transfers to support US foreign and security policy priorities and to take into account whether a given export might increase the possibility of conflict or instability.11 In this way, US arms export law simultaneously encourages supply and advises restraint. Presidential administrations have primary authority over arms exports and also often detail their own additional policy guidance during their time in office. The current Biden administration’s conventional arms export policy outlines a long list of goals for US arms transfers, from selling arms to bolster allies’ security to restraining sales to protect global human rights.12 Although Congress does have an oversight role, US presidents in practice have considerable flexibility in making arms deals,13 and bureaucratic assessments of “downside risks” typically do not influence export decisions.14 Occasional public criticism can promote some restraint at the margins, but US decisions not to sell arms usually stem from political disagreements or security competition. In some cases, the government will impose formal arms embargoes, withholding arms to punish policies and practices which it hopes to change (but suggesting they can be resumed later, once issues are resolved).15

Arms exports are therefore built into US law and policy, which have remained remarkably consistent over time.16 “Decentering” arms sales from US foreign policy in general would require fundamental reforms to US export law, bureaucratic practices, defense industry influence, and policy thinking. What might create the conditions for such change? Most plausible in the short and medium term is that US policy attention may simply shift away from the Middle East to other geographic regions, as the US eyes the return of great power competition, particularly with China in East Asia, and seeks to supply conflicts elsewhere, like Ukraine. Yet, this would merely shift the costs associated with US arms transfers elsewhere and would not resolve issues of demand for weapons by Middle Eastern states. It is also possible that the Middle East, particularly the Gulf, could also become a site of great power competition itself.17

A true “decentering” of US arms sales from US foreign policy would require rethinking three entrenched ideas that underpin the US arms trade and the institutions around it: arms as a signal of support, arms as a source of influence, and the inevitability of alternative suppliers. These ideas help motivate, justify, and shape US interests in arms exports. Their widespread diffusion by government, defense industry, and media actors in US politics and society makes them influential and hard to change. In making this argument, I am not making claims about whether or not these entrepreneurs believe them, or whether or not they are empirically true. What I wish instead is to highlight the challenge of reform in the face of these widespread, interlocking, and deeply entrenched ideas that enhance and extend beyond the significant material influence of lobbyists and military bureaucracy.

1. Arms as a signal of support

Both exporting and recipient states commonly view conventional arms transfers as a sign of practical and symbolic support.18 Former State Department official Andrew Shapiro notes, “[w]hen the U.S. transfers a weapon system, it is not just providing a country with military hardware, it is both reinforcing diplomatic relations and establishing a long-term security partnership.”19 Practically, weapons transfers can bolster military capabilities and enhance alliance interoperability. Since the Vietnam War, the US has also used arms supplies and the training of partner troops as a substitute for deploying its own troops on the ground. Symbolically, providing the means to threaten and engage in war suggests a level of friendship or trust between arms trade partners. As Jennifer Spindel argues, states understand and use arms transfers as signals of the value of their political relationships. Based on the weapons offered by supplier states, she finds, recipient states may reassess their relationship – for better or for worse – with their export partner.20

The “arms as support” idea therefore tends to encourage arms exports, at least to states with which the United States wants to maintain or strengthen political, economic, and/or security ties. Withholding arms to such importers, from this perspective, may damage valuable relationships. In the current international security climate, this idea is likely to gain more traction. If arms sales are perceived as a means to show support (and exert influence – see the next section), the United States will not wish to take actions that risk alienating regional partners and “losing” them to the orbit of its competitors, much like during the Cold War. Moreover, the value of using weapons to signal support is likely to grow as attention returns to military preparedness, alliance cohesion, and concerns about great power war.

2. Arms as a source of influence

Arms sales take on even greater value to US foreign policy in light of the idea that supplying arms provides exporting states with the means to influence the policies and practices of importing states.21 This idea carried particular weight with the United States historically when dealing with Middle Eastern governments in which militaries played a prominent political role,22 and has persisted in the context of post-Cold War US basing and interventions in the region.23 Most recently, proponents credit the Biden administration’s 2021 ban on offensive weapons sales to Saudi Arabia with helping to moderate Riyadh’s behavior in its war in Yemen.24 In general, the “arms as influence” idea suggests that the United States can use weapons sales to help bring importer interests into alignment with its own and provide a source of leverage if not. This idea therefore further enlarges the pool of states to which the United States may find political value in supplying arms, beyond the allies and other importers with whom its interests may already align.

In an era of renewed great power competition, the “arms as influence” idea makes it all the more difficult for the US to “decenter” arms in foreign policy without fearing the loss of a valuable tool when it is most needed. Yet the idea itself is fraught with challenges. First, state interests are often deeply entrenched, and arms transfers are unlikely to easily realign them.25 John Sislin finds that, from 1950-1992, US influence attempts using arms transfers succeeded “slightly less than half of the time” and depended on a complex array of factors, including the target policy type, recipient regime type, and dependence on US arms.26 In 1975, Senator Edward Kennedy cautioned, “it is doubtful that our supplying arms to Persian Gulf states will give us significant influence, much less control, over the way in which these arms are used,” since “the record elsewhere…offers no comfort.”27 More recently, Shana Marshall has pointed out that even the largest recipients of free US arms (Egypt and Israel), “presumably the most dependent on US weapons and therefore most likely to cave to US demands,” consistently violate “the most basic desires of the US foreign policy establishment.”28 Second, the “arms as influence” idea assumes that importers are subject to the will of the exporter. However, because the promised political and economic benefits of arms deals loom large for exporters, importers often wield leverage.29 The Gulf states in particular, Emma Soubrier observes, have showcased enhanced bargaining power in deals with western exporters since the global financial crisis.30 Even so, such deals were cast as economic and political wins for exporters, and the “arms as influence” idea continues to shape export calculations.

3. The inevitability of alternative suppliers

Finally, the idea that other suppliers are always waiting in the wings has made “if we don’t sell it, someone else will” a common refrain among arms exporting states. At its core, this idea justifies arms transfers to recipients engaged in activities that might present legal or normative cause for export restraint (e.g., severe human rights violations or conflict), on the grounds that denying transfers will not prevent those recipients from acquiring weapons elsewhere. However, this idea also interacts with the “arms as support” and “arms as influence” ideas, complicating matters for policymakers. If the US steps out of the game, from this perspective, it means not only that the recipient will still get the weapons, but also that the alternative supplier(s) will reap the signaling and influence benefits of arms transfers instead of the US.

As great power competition intensifies, the “inevitability of alternative suppliers” idea will become particularly potent. As Elias Yousif notes, US policymakers have effectively argued that efforts to limit arms transfers to the Middle East “would provide a dangerous opening for the likes of China or Russia to supplant the United States as the security partner of choice for these erstwhile allies, thereby drawing them into competing spheres of influence.”31 In Africa, for example, China supplies weapons with less attention to human rights, leaving US officials concerned about shifting allegiances.32 However, while switching suppliers is possible, it comes with financial, operational, and relationship costs to recipients,33 making it far from inevitable. Moreover, Gulf states may have other reasons to diversify their arms sources, “as part of their strategies to increase their level of autonomy and self-determination and increasingly project this newfound power – and influence – outside of their borders.”34 Fence-sitting governments in the Global South may also pursue diversification, rather than replacement, of arms suppliers as part of their hedging strategies.35 Thus, while alternative (or additional) suppliers certainly exist, it seems unlikely that long-standing recipients will choose to sever arms-transfer ties with the United States in the short or medium term. Whether these ties bring genuine support or influence benefits to the US, however, remains a separate question.

Conclusions

The international political and security environment is changing. Accelerating US-China security competition, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the modernization and expansion of nuclear arsenals, growing transactionalism, and doubts about the reliability and longevity of US political commitments have left arms transfers perceived as an increasingly relevant currency of international politics. Rather than prompting policymakers to rethink long-standing ideas about arms transfers and their benefits, these security conditions reinforce them. Deeply entrenched ideas are hard to change under more favorable conditions, and the current geopolitical climate is hardly favorable. This is not only true for exporters. For importers, arms are also viewed as signals of support and partnership, as well as symbols of prestige and modernity, and necessary for security. A more militarized global environment will only strengthen these ideas, not diminish them. Simply put, the demand for arms, and governments’ willingness to supply them, are unlikely to go away any time soon.

In a time of regional and global security concerns, discussions about how to decenter arms transfers in the Middle East are therefore both important and challenging. Achieving this would likely require both structural and ideational shifts. One possible scenario is that the United States refocuses its security relationships and accompanying resources away from Middle Eastern states to other regions it considers more critical in its competition with China. Lucie Béraud-Sudreau, for example, anticipates a return to Cold War-like arms trade patterns with weapons and technology transfers restricted to political blocs.36 Production limitations may also help this scenario along.37 However, this would not necessarily reduce arms flows to the Middle East or US arms transfers overall. Middle Eastern demand would find other suppliers, and US supplies would go elsewhere.

The more challenging scenario involves a more fundamental devaluation of the role of the arms trade in international politics and strategic partnerships. In that case, how can advocates of arms export restraint create and institutionalize ideational change – and do so under difficult conditions? Simply showcasing the frequent disconnect between the promised versus realized political and economic benefits of the arms trade is not enough; restraint advocates have been doing this for years. Scholarship suggests that US decision-makers would collectively have to acknowledge that existing ideas about the arms trade are inadequate, discredited, or harmful, and collectively agree on new replacement ideas.38 Advocates, as policy entrepreneurs, can seek to shape such replacement ideas. With this in mind, a dramatic and costly failure of US arms trade policy, coupled with coordinated efforts by advocates to promote new ideas among networks of key decision-makers may be the best conditions to create meaningful change in US arms exports to the Middle East.

1The author thanks Ava Podany for her excellent research assistance.

2For an overview, see Thomas, C. et al. (2020). Arms Sales in the Middle East: Trends and Analytical Perspectives for U.S. Policy. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service.

3See for example Perlo-Freeman, S. (2024). “Can the UK Kick its Addiction to Middle East Arms Sales?” PRISME Initiative; Pinson Hindawi, C. (2024). “‘Stop Arming Israel – France’ and Broader Attempts to Expose the Military Dimensions of the French High-Tech Industries and Partnerships”. PRISME Initiative; Stavrianakis, A. (2024). “The Demand for Conversion: From ‘Economics versus Ethics’ to ‘Economics with Ethics’”. PRISME Initiative.

4See for example Hartung, W.D. (2022). “Promoting Stability or Fueling Conflict? The Impact of US Arms Sales on National and Global Security”. Quincy Institute. Available at: https://quincyinst.org/research/promoting-stability-or-fueling-conflict-the-impact-of-u-s-arms-sales-on-national-and-global-security/; Markusen, A. (1992). “Dismantling the Cold War Economy.” World Policy Journal, 9(3), 389-99; Neuman, S.G. (2010). “Power, Influence, and Hierarchy: Defense Industries in a Unipolar World.” Defence and Peace Economics, 21(1), 105-134; Pierre, A.J. (1982). The Global Politics of Arms Sales. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; Smith, P.J. (2020). “Arms Exports and U.S. Grand Strategy: Understanding the Nexus.” In Research Handbook on the Arms Trade, ed. A.T.H. Tan.

5Warren, for example, finds “672 cases in 2022 in which the top 20 defense contractors had former government officials, military officers, Members of Congress, and senior legislative staff, working for them as lobbyists, board members, or senior executives,” 91% of which “became registered lobbyists for big defense contractors”. Warren, E. (2023). Pentagon Alchemy: How Defense Officials Pass Through the Revolving Door and Peddle Brass for Gold. Available at: https://www.warren.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/DoD%20Revolving%20Door%20Report.pdf, 2-3.

6For an overview, see Thrall, A.T. et al. (2020). “Power, Profit, or Prudence? US Arms Sales since 9/11.” Strategic Studies Quarterly, 14(2), 100-126.

7Wezeman, P.D. et al. (2024). Trends in International Arms Transfers, 2023. SIPRI Fact Sheet. Available at: https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2024-03/fs_2403_at_2023.pdf, 3). The study further finds that total arms imports by countries in the Middle East were down 12% in 2019-2023 compared to 2014-18 (11).

8Note that this reflects a broader trend: total arms imports by countries in the Middle East were down 12% in 2019-2023 compared to 2014-18 (Wezeman et al. 2024, 11).

9Wezeman et al. (2024, 11).

10Data from the SIPRI Arms Transfers Database, accessed 22 June 2024.

11For a brief overview, see Erickson, J.L. (2023). “Demystifying the ‘Gold Standard’ of Arms Export Controls: US Arms Exports to Conflict Zones.” Global Policy, 14, 131-38.

12Biden, J. (2023). Memorandum on United States Conventional Arms Transfer Policy. National Security Memorandum 18. Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2023/02/23/memorandum-on-united-states-conventional-arms-transfer-policy/

13Erickson (2023). Indeed, Congress has never managed to muster enough votes to a suspend major US arms deal. The closest it came was in 2019, when it passed bipartisan legislation to block weapons sales to Saudi Arabia but did not have enough votes to overcome the inevitable presidential veto.

14Thrall et al. (2020).

15Erickson, J.L. (2020). “Punishing the Violators? Arms Embargoes and Economic Sanctions as Tools of Norm Enforcement.” Review of International Studies, 46(1), 96-120.

16Erickson, J.L. (2015). “Saint or Sinner? Human Rights and U.S. Support for the Arms Trade Treaty.” Political Science Quarterly, 130(3), 449-74.

17See Sheline, A. (2024). “Multipolarity & Military Spending”. PRISME Initiative; Ulrichsen, K.C. (2024). “Saudi Arabia, Iran, and the Search for a Durable Regional Consensus”. PRISME Initiative.

18See for example: Pierre, A.J. (1981). “Arms Sales: The New Diplomacy.” Foreign Affairs, 60(2), 266-86; Soubrier, E. (2020). “The Weaponized Gulf Riyal Politik(s) and Shifting Dynamics of the Global Arms Trade.” The Economics of Peace and Security Journal, 15(1), 49-57; Spindel, J. (2018). Beyond Military Power: The Symbolic Politics of Conventional Weapons Transfers. Doctoral dissertation, University of Minnesota; U.S. Department of State (USDOS) (2023). FMS 2023: Retooling Foreign Military Sales for An Age of Strategic Competition. Available at: https://www.state.gov/fms-2023-retooling-foreign-military-sales-for-an-age-of-strategic-competition/; Yarhi-Milo, K. et al. (2016). “To Arm or to Ally? The Patron’s Dilemma and the Strategic Logic of Arms Transfers and Alliances.” International Security, 41(2), 90-139.

19Shapiro, A.J. (2012). “A New Era for U.S. Security Assistance.” The Washington Quarterly, 35(4), 23-35, 29.

20Spindel (2018).

21See for example: Kennedy, E.M. (1975). “The Persian Gulf: Arms Race or Arms Control?” Foreign Affairs, 54(1), 14-35; Krause, K. (1991). “Military Statecraft: Power and Influence in Soviet and American Arms Transfer Relationships.” International Studies Quarterly, 35(3), 313-36; Sislin, J. (1994). “Arms as Influence: The Determinants of Successful Influence.” Journal of Conflict Resolution, 38(4), 665-89; Thomas et al. (2020).

22Paul, J. and Stork, J. (1983). “Arms Sales and the Militarization of the Middle East.” Middle East Report, 112 (February). Available at: https://merip.org/1983/02/arms-sales-and-the-militarization-of-the-middle-east/. Note, however, that Sislin (1991) finds that such influence attempts are in practice more likely to succeed with civilian, not military, regimes.

23Marshall, S. (2020). “The Defense Industry’s Role in Militarizing US Foreign Policy.” Middle East Report, 294. Available at: https://merip.org/2020/06/the-defense-industrys-role-in-militarizing-us-foreign-policy/

24Dent, E. & Rumley, G. (2024). “How the U.S. Used Arms Sales to Shift Saudi Behavior.” The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Available at: https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/how-us-used-arms-sales-shift-saudi-behavior.

25Erickson (2023). While exporters could threaten the prospects of future sales, they are unlikely in practice to impose arms embargoes against arms trade partners (Erickson 2020).

26Sislin (1991, 681-82.

27Kennedy (1975), 28.

28Marshall (2020).

29See for example Soubrier (2020), “The Weaponized Gulf Riyal Politik(s)”, 49; Soubrier, E. (2019). “Global and Regional Crises, Empowered Gulf Rivals, and the Evolving Paradigm of Regional Security.” POMEPS Studies, 34, Available at: https://pomeps.org/global-and-regional-crises-empowered-gulf-rivals-and-the-evolving-paradigm-of-regional-security; Spindel, J. (2023). “Arms for Influence? The Limits of Great Power Leverage.” European Journal of International Security, 8(3), 395-412.

30Soubrier (2020), “The Weaponized Gulf Riyal Politik(s)”, 49; Soubrier (2019).

31Yousif, E. (2023). “The Fear of Missing Out – Reconsidering Assumptions in US Arms Transfers to the Middle East.” PRISME Initiative. Available at: https://prismeinitiative.org/blog/fear-of-missing-out-elias-yousif/; Yousif, E. (2023). “‘If We Don’t Sell It, Someone Else Will’: Dependence and Influence in U.S. Arms Transfers.” The Stimson Center.

32“Arms for Africa” (2024), The Economist, 25 May; see also Page, J. & Sonne, P. (2017). “Unable to Buy U.S. Military Drones, Allies Place Orders with China.” Wall Street Journal. Available at: https://www.wsj.com/articles/unable-to-buy-u-s-military-drones-allies-place-orders-with-china-1500301716.

33Palik, J. & Marsh, N. (2024). Arming Saudi Arabia: Navigating the Paradox of Power and Vulnerability. Mideast Policy Brief 02. Oslo: PRIO Middle East Centre; Yousif (2023), “The Fear of Missing Out” and “‘If We Don’t Sell It, Someone Else Will’”.

34Soubrier, E. (2020), Gulf Security in a Multipolar World: Power Competition, Diversified Cooperation. Issue Paper 2. Washington, DC: The Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington, 10.

35Spektor, M. (2023). “In Defense of the Fence Sitters.” Foreign Affairs, May/June. Available at: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/print/node/1130117.

36Béraud-Sudreau, L. (2024). “The New Geopolitics of Arms Transfers”. In The Palgrave Handbook of Contemporary Geopolitics, ed. Z. Cope: 1-17.

37On current US and Russian production limitations, see “Past Their Prime” (2024), The Economist, 13 July and “Running Out” (2024), The Economist, 20 July.

38See Berman, S. (2001). “Ideas, Norms, and Culture in Political Analysis.” Comparative Politics, 33(2), 231-50; Legro, J.W. (2000). “The Transformation of Policy Ideas.” American Journal of Political Science, 44(3), 419-32.