Arms Sales & Transfers Generate Powerful Constituencies for Continued Weapons Flows, while Diplomatic and Non-Military Forms of Engagement are Marginalized

Weapons transfers are a central feature of international affairs, but often considered a ‘lesser’ form of intervention and an alternative to deploying soldiers. The arms industry is often treated by analysts and scholars as a technocratic or commercial concern that has no direct influence on ‘real’ IR issues like declarations of war and direct military invasions. This perspective is shortsighted, since the organization and functions of arms industries intersect directly with foundational inquiries into the nature of states, markets, and military power.1 It may seem counterintuitive, but the more central weapons have become to the practice of international affairs, the less they’ve been recognized as such in scholarly analysis. If we are to dislodge the power and influence of the global arms industry and the role that weapons play in guiding international affairs, we must make these actors central to our analyses.

This downplaying of the political influence of the military industrial complex is especially problematic now, as the steady globalization of weapons production has created a transnational industry driven by a new constellation of incentives. In the Global North, shareholder capitalism, which prioritizes returns to capital (often through stock buybacks) over reinvestment in business operations, has diminished state control over the military industrial sector. Simultaneously, the shift to multipolarity means that weapons conglomerates originating in the capitalist core of Europe and the United States increasingly rely on export revenues and Global South markets for growth. Key sites of concentrated capital outside the core, such as major oil-exporting states, are actively funding industrial and technological expansion to produce new weapons on their own turf –making them attractive partners for major arms companies. The factors enabling these changes – the growing influence of shareholder capitalism over the state, the role of global finance (including private equity and venture capital) in militarizing the tech industry, and the dramatic expansion and complexity of global supply chains for weapons manufacturing across the Global South – are key to understanding current trends in arms production and the MENA region’s role in this new system. It is no coincidence that the region is simultaneously the epicenter of recurring large-scale military invasions and bombing campaigns, the frontier for expanding weapons production lines and testing emerging technologies, and the major source of capital fueling the industry’s global growth.

Much like the global arms trade itself, the Global South is often overlooked as a hub of influence in the international system, let alone as an important agent in the global arms industry. Most political economists are very familiar with the distributed and diffuse financing networks and supply chains involved in, for example, the apparel industry, and the Global South’s key role in that sector. But far fewer are aware that many Raytheon missile components are produced in the same Mexican border towns that figure centrally in our discussions of industrial sweatshops and free trade agreements, or that major transnational weapons firms are increasingly locating both corporate offices and manufacturing and research centers beyond their traditional host states in the United States and Europe, in places like the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Saudi Arabia.2

Global South and South-South weapons collaboration are central to emerging multipolar order

Weapons collaboration among MENA states, and between MENA states and the broader Global South, is embedded in a larger emerging system of multipolarity being driven by anti-imperialist politics. This includes reactions to U.S. sanctions, that have spurred efforts toward de-dollarization and the development of South-South payment systems, as well as large-scale development initiatives led by China and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) States. As Omar Dahi highlights in his PRISME paper, the massive technological gaps that once separated the industrialized North from the agrarian or de-industrialized South have narrowed significantly.3 Several states in the Global South are now emerging as hubs of innovation in fields such as computing, infrastructure design, medical technologies, and, of course, weapons development. This reduction in technological disparities has facilitated greater trade and manufacturing collaboration. Advances in shipping, information technology, and communication have further supported these developments, as has the availability of financial resources from state-owned oil and gas exporters, particularly the GCC States.

The influence of the Global South has risen in tandem with for a renewed embrace of a more expansive role for the state in economic planning and industrial policy (even in Global North states). This shift has enabled countries in the Global South to become major exporters of technologically advanced products like automobiles, electronics, and renewable energy equipment, now accounting for 55% of this trade worldwide.4 This transformation is not merely a reflection of multinational firms relocating production to the Global South to capitalize on cheaper labor, land, and other inputs. It also reflects the rise of many home-grown firms and regional hubs specializing in high-skill, capital intensive sectors, such as tech innovation in Kenya’s “Silicon Savannah,” financial products in Dubai, and automobile manufacturing in India, South Korea, and China. Government-led industrial policies, which include the provision of public funds, physical infrastructure, commercial/export assistance, subsidized inputs (energy, land, intermediate imports), investment in R&D facilities, vocational training, and other investments, have had a very visible impact in the resulting expansion of indigenous military industrial production.

In the GCC, particularly in the UAE, this is reflected in the steady consolidation of defense industrial firms under state-owned conglomerates and the increasing presence of so-called “landed” companies, which are wholly self-owned subsidiaries, usually operating in free zones, where they can actively engage with the domestic defense and security industry, employ local Emirati labor, and export products labeled “Made in the UAE.”5 At least two major multinational weapons firms – Saab and Raytheon – have such arrangements in the UAE.6 The incorporation of such large firms into the domestic manufacturing landscape generates significant spillover opportunities for other local firms, which become suppliers and subcontractors for new products in military, security, surveillance, and related sectors. One example is Strata manufacturing, part of the UAE’s state-owned defense conglomerate, which manufactures airplane parts for both Boeing and Airbus7.

Such partnerships are equally appealing to multinational defense firms, offering proximity to critical markets in the Middle East and Africa and providing a long-term strategy to circumvent arms export controls by developing and manufacturing outside the original host country. For instance, if such a landed company develops new technologies at research facilities in the UAE (and the country does boast extremely sophisticated labs and testing facilities, often provided under earlier offset agreements), then those technologies would likely not be subject to export controls from the firm’s home country, including International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) regulations. In reference to its new landed company in the UAE, Saab noted, “[w]e would also like to develop our IP outside of Sweden to create new markets and increase our total market access.”8 This strategy is particularly attractive in states (like the GCC countries) which possess substantial financial resources to provide facilities and other forms of support to defense firms. Instead of limited joint ventures, these landed companies become permanent partnerships that fully incorporate GCC-based producers into the transnational supply chains of major weapons platforms, furthering the militarization of existing domestic manufacturing bases and training programs.9 As these states expand their roles in supplying materials and sophisticated components for these major platforms, blocking exports of finished products to these states on humanitarian or strategic grounds becomes increasingly challenging. Moreover, despite claims from industry advocates and lobbyists, such weapons partnerships rarely generate the positive ‘spillover’ effects into civilian manufacturing and technological development they frequently promise. Consequently, the potential gains in human and physical capital development are unlikely to contribute to the GCC’s broader economic diversification plans.10

These so-called “landed companies” represent a unique innovation in the globalization of the military-industrial complex. Although such ‘landed’ partnerships between U.S. and European manufacturers are common (examples include BAE Systems of the United States and Raytheon UK, both 100% foreign-owned), similar arrangements outside these transatlantic frameworks appear rare. The Middle East is therefore unique in this regard, as hosting the only landed military companies in the Global South. Saudi Arabia’s much-hyped 2022 policy that would require all foreign firms operating in the kingdom to establish their regional headquarters within its borders appears to have caused a somewhat similar outcome. The policy catalyzed major supply contracts for domestic Saudi firms to manufacture key components for a range of high-end weapons systems, including Lockheed Martin’s Terminal High Altitude Air Defense System.11

These arrangements also appear to facilitate violations of arms control measures, notably the ITAR. In a recent U.S. corruption ruling against Raytheon (now RTX), the discovery process revealed a number of violations involving the transfer of sensitive defense articles, components, and technical data to the UAE.12 Foreign firms can also circumvent export restrictions entirely by relocating their entire production lines to the region, enabling them to secure lucrative GCC contracts without the constraints of home-country regulations. In 2008, Streit Group, a manufacturer of armored vehicles originally located in Canada, made a sale to the UAE of vehicles that had been retrofitted in the United States. It is likely that Streit Middle East (UAE) was established around this time and in connection with this sale. Since then, Streit has relocated significant parts of its manufacturing capacity to the UAE, and the armored vehicles it produced there were sold or transferred to embargoed countries including Libya and Sudan.13 Despite Streit’s origin as a Canadian company, Canadian courts claim they have no jurisdiction over its operations because production now takes place in the UAE.

Another example is Calidus, a UAE aerospace company which sought to secure technology from Dassault for use in its prototype B-250 light attack aircraft. When this effort proved unsuccessful, the UAE instead acquired Brazil’s airplane manufacturer Novaer to obtain the technology used in the SuperTucano, the plane on which the B-250 is based. In 2019, Calidus partnered with a Saudi firm to market the plane to Riyadh and other MENA countries. The plane’s knockdown kit allows it to be disassembled and reassembled within 24 hours and transported intact in the hull of a C-130, making it particularly suitable for supporting special operations in remote areas of the Sahel, where the UAE’s presence is growing. According to industry reports, the explicit goal of the acquisition was to further efforts at developing systems that are not subject to ITAR.14 In addition to removing obstacles to export and expanding indigenous technological development, such partnerships are viewed by many countries as a safeguard against potential sanctions or supply restrictions. When asked about the impact of weapons embargoes over Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen, the CEO of SAMI (Saudi Arabia Military Industries) said: “If the U.S. blocks us, we still have the opportunity for almost any of the products and any of the weapon systems to get it (sic) localised through our partnerships. Opportunities can be European, Asian, South African and Far East sources.”15

This general trend suggests heightened expansion of the transfer of weapons technology resulting in the domestic provision of more equipment for use in regional conflicts outside the traditional bounds of great power proxy conflicts. The range of motivations for increasing the production of weapons inside the MENA is broad, and the mechanisms available are equally so. According to one UAE official working on military industrial collaboration in the country’s defense offset bureau,

“Contractors can make investments. They can form traditional, equity joint ventures, or produce partnerships without equity such as co-production or technology co-development. They can also form contractual engagements, signing a work package contract with a local supplier or manufacturer. They could manufacture products in the UAE for export, for example, provide services to foreign buyers, or create supply opportunities for local industry. They can also transfer technology or provide training to Emirati nationals.”16

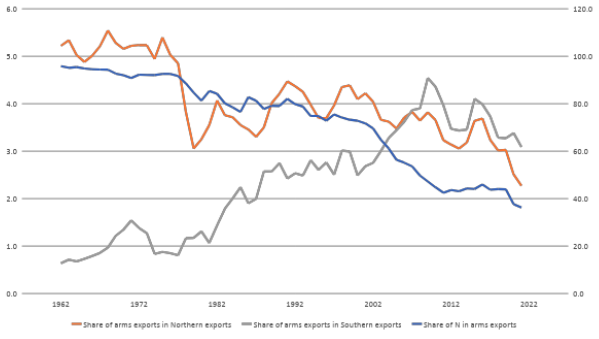

The result of any of these policies is that the weapons systems may be available locally and for export without being subject to sanctions, arms trade regulations, or reliance on any one patron state’s supply capabilities. This model also circumvents supply chain interruptions or other logistical obstacles. The general trend in rising arms exports (as a share of overall exports) from the Global South is visible in the first graph below, where the gray line depicts the growing proportion of arms in exports coming from the Global South, and both the orange and blue lines shows the Global North’s decreasing relative share. This does not, unfortunately, mean the Global North’s manufacturing base is becoming less militarized. Rather, it reflects the increasing dominance of financial products exports (aka, financialization) in the Global North’s economies.17

Figure 1: Share of Arms Exports in North and South Overall Exports (1962-2021)18

Source: Firat Demir, based on an unpublished paper.19

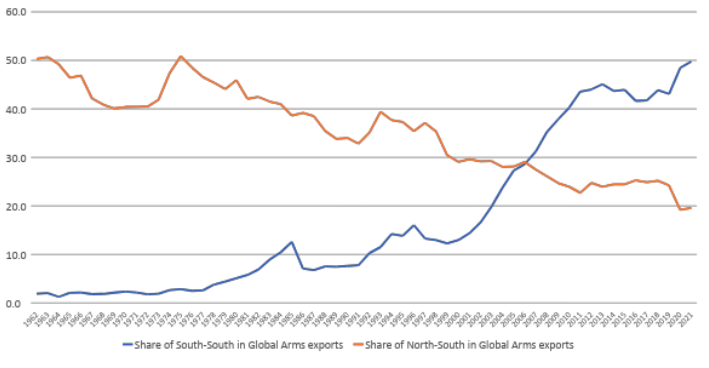

Simultaneously, trade in arms between Global South countries is expanding as a share of the overall arms trade, with a corollary decline in the Global North’s role in supplying the Global South. The second graph, below, shows that about 50% of arms exports to the Global South in 2021 came from other Global South countries.

Figure 2: Share of South-South and North-South in Global Arms Exports (1962-2021)

Source: Firat Demir, based on an unpublished paper.20

Capital as a Node in the Emerging Multipolar Order and How Finance is Driving Weapons Development

A critical factor in the expansion of weapons production is the increasing role of new global centers of finance capital. Historically, industrial and scientific assets for military production were almost exclusively located in core capitalist countries and organized by industrial giants through state-led industrial policies. Today, however the bleeding edge of this activity is located elsewhere. This is especially evident in the era of AI-driven weapons development. The specialized chips, server centers, and vast computing power required for these systems are not only extraordinarily expensive but also heavily energy intensive. These weapons demand vast reservoirs of finance capital that are not constrained by the short-term revenue pressures or shareholder demands typical of public companies. These reservoirs include:

Venture Capital (VC): Many VC funds, long heavily capitalized by financial flows from the GCC, are extremely active in backing weapons development, particularly in the realm of so-called ‘defense tech’.21

Private Equity (PE): PE funds are investing increasingly large sums in military and security firms, often acquiring majority shares. This practice transforms publicly traded companies—subject to beneficial ownership disclosure rules and regular shareholder reporting—into black boxes where neither the source of funding nor the firm’s activities are subject to any meaningful scrutiny.

State investment funds (aka sovereign wealth funds): In addition to financing VC and PE funds, these state-backed reservoirs provide direct funding for weapons development and manufacturing initiatives in the Global South.

Philanthropic foundations and non-profits: The military industrial complex and its Silicon Valley allies exploit U.S. tax regulations to divert revenues into organizations like foundations and non-profits, which serve as socially acceptable vehicles for promoting their interests, such as tax breaks for AI data centers and lavish research fellowships for scientists aligned with industry goals.

The GCC States’ extraordinary capital reserves make them key players in the weapons-finance capital nexus. In March 2024, Saudi Arabia’s major state-owned fund PIF announced a $40 billion partnership with the Silicon Valley venture capital firm Andreesen Horowitz (itself one of the largest VC investors in military tech) to fund advancements in AI.22 Similarly, the UAE’s state-backed intelligence firm G42, itself heavily invested in AI technologies, received a $1.5 billion investment from Microsoft in late 2023. This deal, which had formal backing from both Abu Dhabi and Washington, required G42 to sever its ties with Huawei, the Chinese company that had previously provided its cloud storage.23 This is critical because G42, chaired by Sheikh Tahnoon bin Zayed, the UAE’s national security advisor, essentially operates as the country’s de facto intelligence agency.

GCC state capital is also driving military industrial and technological expansion in the rest of the Global South. One way is through providing loans to cash strapped countries with sophisticated domestic military industries. Serbia offers a compelling example. In 2013, the UAE provided Serbia with several billion dollars in loans on highly preferential terms, including low interest rates and flexible repayment conditions.24 The UAE also invested directly in Serbia’s arms industry, including through direct deals between Serbian weapons manufacturers and their Emirati counterparts, and initiated programs to cooperate in military police, special forces, and cyber defense.25 In parallel, the UAE and Saudi Arabia purchased large quantities of Serbian-made weapons, including armored vehicles, ammunition, and mines, while the UAE made investments in Serbian missile manufacturers.26 Because Serbia has a sophisticated – but loosely regulated – arms industry as well as a large inventory of surplus equipment,27 it enables the UAE (and other GCC States) to acquire weapons they can easily re-export as a means of garnering influence and directing neighboring conflicts toward their preferred outcome. This collaboration has deepened over time. In 2022, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar made large investments in a fund aimed at promoting Serbian tourism, and in 2024, Serbia held military exercises using UAE-made drones manufactured by EDGE, the UAE’s state-owned defense conglomerate.28

Conclusion

Several factors are fundamentally reshaping the global development and transfer of weapons: the globalization of production lines and supply chains; increased technological development in the Global South that has created more sites for high tech arms production; heightened competition among weapons manufacturers seeking to increase market share in the Global South, catalyzed by the political and economic decline of the United States and Europe; and the growing interest of global finance in the military tech sector. The latter trend is increasingly stark as the era of ‘free money’ driven by historically low interest rates has come to an end, while rates of innovation for non-military tech products and services have plateaued. Together, these changes suggest that the GCC States will play an increasingly pivotal role in shaping the future of weapons development, patterns and flows of purchases and transfers, and an emerging era of arms-race-driven conflicts.

Decentering arms production, collaboration, and transfers will require unwinding a global system in which weapons have become the primary conduit for political and commercial engagement between states. Security alliances and bilateral security agreements often contain lofty language about peace and prosperity, yet they are operationalized primarily through the transfer of lethal equipment and personnel. At the same time, substantial political capital and legal resources are devoted to advancing weapons technology transfers, while technologies such as pharmaceutical innovations or climate mitigation strategies, which could genuinely enhance human security, lack comparable champions in the halls of power. During the heyday of Third World solidarity movements, epitomized by the Bandung Conference and the creation of the Non-Aligned Movement and the G-77, oil-rich states were envisioned as the key to reforming an international system whose institutions and norms operated solely to reproduce the political and economic hegemony of the Global North.29 If the emerging multipolar order can recapture some of the momentum and optimism of that earlier era, it may be possible to pull the GCC States into a system that promotes technologies and investments aimed at averting ecological catastrophe and fostering human flourishing. Achieving this vision, however, will depend heavily on whether leaders and publics in the Global North can recognize their shared fate and pivot away from a trajectory of militarization and confrontation. Only by disengaging from these patterns can a path to collective survival be charted.

1Bryan Maybee, 2009. The Security State and the Globalization of the Arms Industry, Palgrave MacMillan, p. 88.

2See Shana Marshall, 2016. “Military Prestige, Defense-Industrial Production, and the Rise of Gulf Military Activism” in Armies and Insurgencies in the Arab Spring, Holger Albrecht, Aurel Croissant and Fred H. Lawson (eds), University of Pennsylvania Press.

3Omar Dahi, 2023. “South-South Trade in Arms: New Frameworks Needed?” PRISME Initiative. https://prismeinitiative.org/app/uploads/2023/11/dahi-south-south-trade-in-arms.pdf

4Ibid.

5Although Emiratization of the labor force is a key political issue, the extent to which this exists in the defense industry is unclear. According to SIPRI data, transfers of military items from the UAE are primarily modified armored vehicles and UAVs to a limited number of MENA and African countries, including Algeria, Egypt, Morocco.

6Countertrade & Offset Newsletter, April 12, 2021. Defense firms define landed companies as “those companies sharing a large corporate name but with independent operating structures in overseas locations.” See Kenneth Peters, 2018. “Strategies for Improving Contractors’ Defense Acquisition Cost Estimates,” Doctoral Dissertation, https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=7372&context=dissertations

7Airbus press release 25 November 2019. “Airbus and Strata celebrate 10-years of partnership shaping UAE’s aerospace industry,” https://www.airbus.com/en/newsroom/press-releases/2019-11-airbus-and-strata-celebrate-10-years-of-partnership-shaping-uaes

8Countertrade & Offset Newsletter, April 12, 2021

9According to Fahad Mohammed Al Mheiri, the Managing Director of Raytheon Emirates, the company is “investigating opportunities to qualify second-source suppliers in the UAE that would contribute to Raytheon Technologies’ product lines,” 1 February 2023, Al-Jundi, https://www.aljundi.ae/en/interviews/fahad-al-mheiri-managing-director-raytheon-emirates-for-al-jundi-we-contribute-to-building-the-defence-capabilities-of-the-uae-the-employment-of-its-national-cadres/

10See Omar al-Ubaydi, 2023. “The Potential Drawbacks Associated with Domestic Military Manufacturing in the GCC Countries,” PRISME Initiative, https://prismeinitiative.org/blog/potential-drawbacks-gcc-military-manufacturing-omar-al-ubaydli/

11“Lockheed Martin Awards Localization Subcontracts For THAAD Weapon System In The Kingdom Of Saudi Arabia” Lockheed Martin Press Release, 5 February 2024, https://news.lockheedmartin.com/2024-02-05-Lockheed-martin-awards-localization-subcontracts-for-thaad-weapon-system-in-the-kingdom-of-saudi-arabia

12“RTX Corporation Reaches Record $200 Million Settlement with DDTC for Serial Violations of the AECA and ITAR,” JD Supra, 6 September 2024, https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/rtx-corporation-reaches-record-200-3998840/

13“Order Relating to Streit Group FZE and Streit Middle East FZCO,” 1 September 2014, U.S. Bureau of Industry & Security, https://efoia.bis.doc.gov/index.php/documents/export-violations/export-violations-2015/1023-e2435/file

14“Why the Calidus truly is the light fantastic,” undated, Times Aerospace, https://www.timesaerospace.aero/features/defence/why-the-calidus-truly-is-the-light-fantastic

15Countertrade & Offset Newsletter, February 3, 2020.

16Countertrade & Offset Newsletter, April 12, 2021

17Lisa Donner, “Disentangling the economy from neoliberal financialization,” 9 August 2023, Hewlett Foundation, https://hewlett.org/disentangling-the-economy-from-neoliberal-financialization/

18The share of arms exports in overall Northern exports and the share of arms exports in overall Southern exports are on the left axis. The share of North in arms exports is on the right axis and shows the share of North in total/global arms exports.

19Firat Demir and Zachary Zaslavsky, “Utilizing Harmonized System Codes to Track the Trade of Arms and Strategic Goods”, unpublished manuscript.

20Ibid.

21Shana Marshall, 2024. “How Venture Capital is Busting the Military Industrial Complex – for its own benefit,” Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft. https://responsiblestatecraft.org/venture-capital-military-industrial-complex/

22“Saudi Arabia Plans $40 Billion Push Into Artificial Intelligence”, 19 March 2024, New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/03/19/business/saudi-arabia-investment-artificial-intelligence.html

23Karen Kwok, “Microsoft’s G42 deal puts UAE in America’s AI tent” 17 April 2024, Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/breakingviews/microsofts-g42-deal-puts-uae-americas-ai-tent-2024-04-16/

24Neil Buckley, “Serbia seeks billions in loans from UAE amid bankruptcy fears, 7 October 2013, Financial Times, https://www.ft.com/content/672a7b1c-2f4a-11e3-8cb2-00144feab7de. Serbia used these initial loans to pay off high interest debt incurred from other lenders as a result of the global financial crisis, and to invest in key domestic sectors like agriculture and its national airline. As details of the loans later made clear, much of the ‘investment’ was actually credit notes that gave the UAE equity shares in new enterprises, put Belgrade on the hook for all potential losses, put large swaths of fertile agricultural land in Emirati hands, and guaranteed the UAE privileged access to Serbian markets.

25Rory Donaghy, “The UAE’s shadowy dealings in Serbia,” 12 February 2015, Middle East Eye, https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/uaes-shadowy-dealings-serbia

26“UAE-linked company in Serbia supplying weapons to Israel amid war on Gaza” 1 July 2024, Middle East Eye, https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/uae-linked-serbian-company-supplying-weapons-israel-amid-war-gaza

27Donaghy, “The UAE’s shadowy dealings in Serbia”

28Igor Bozinovsky, “Serbian exercise demonstrates UAE-supplied and indigenously developed loitering munitions” 5 July 2024, Janes Defence, https://www.janes.com/osint-insights/defence-news/air/serbian-exercise-demonstrates-uae-supplied-and-indigenously-developed-loitering-munitions

29Giuliano Garavini [interview], “OPEC Was First Formed as a Challenge to Western Energy Dominance” 7 September 2023, Jacobin Magazine, https://jacobin.com/2023/09/opec-founding-decolonization-oil-production-western-imperialism